Unleashed Memoir #8 / Part I: Phnom Penh denouement

Surrounded by the Khmer Rouge, flight from the inferno … and onward ….

On October 6, 2024, with my beloved wife of the past quarter century—Pamela—I celebrated the 80th anniversary of my presence on this planet among my fellow citizens of the world. As it happens, it also marked the half century (50 years) since I embarked on my life as a foreign correspondent, observer, and chronicler of more than 90 lands far from my own. To commemorate this, another moment from my own past, frozen in time, you will find here an excerpt from my memoir, "Don't Shoot, I'm an American Reporter,” which is still being written. From time to time, Unleashed Memoir will present excerpts from this work where and when they resonate especially. And in this excerpt, I am now deep within the inferno that was Cambodia just 50 years ago.

In Phnom Penh, it's deeply into this war of survival….no less than for myself.

On March 5, 1975, Syd Schanberg decided that it was time for me to visit “the front,” so he agreed to relinquish our interpreter/photographer Dith Pran for a day. Pran found us two motorbikes, and with each of us riding pillion, we set off down Highway One on the west bank of the Tonle Sap River. I was wearing large sunglasses, a denim work shirt, a pair of pretty worn chinos and canvas jungle boots. My driver was wearing a tan jungle shirt, jeans, a flat worker’s cap not dissimilar to the ones sported by the Khmer Rouge, and flipflops. Without sunglasses, he squinted into the wind as we ripped down the rutted dirt road that passed for a highway. Just a couple of miles south of town, we pulled to a stop by a small village—basically a collection of a half dozen huts and a few roadside stands. A dirt track ran down into the brush on the left and Pran asked the locals if it was safe. They assured him that if we halted at a wat a mile or so into the jungle, we’d be fine and that there, we’d find the forward command post for a small platoon of “our” forces that had engaged the Khmer Rouge seeking to move forward.

We set off down the road and, sure enough, 20 minutes later, we came upon the wat. Inside were a young Cambodian captaiin, Van Dy, and his communications aide with a heavy combat radio. Pran struck up a conversation. There was gunfire out beyond the clearing where we crouched. The captain pointed across to a tree line not so far away where his forces had engaged the Khmer Rouge. He was on and off the radio regularly but seemed relatively unconcerned. What he was concerned about, as I reported the next day in The Times, was the nature of the recruits he’d been receiving. With repeated battlefield reverses, morale had been plummeting. “The new troops are so afraid,” Captain Van observed.

Commissioned to hold a critical line outside the town of Tuol Leap, he’d lost a third of his forces since the first of the year when the Khmer Rouge had begun their offensive, overrunning the town just the previous Friday. “They do not want to fight,” he said, describing his demoralized men, “and they want to be paid. So, they leave the unit to go back to Phnom Penh for their paychecks.”

His troops were engaged, as we spoke, with what he described as a “probing force.” His fear was that the 2,000 strong main force of enemy troops might again press his depleted brigade of barely 900 men before the week was out. After an hour or so of conversation, we smiled, shook hands and said we thought we’d go.

“Not the way you came in, I’m afraid,” the colonel smiled thinly. What? Seems that while we were chatting, the KR had circled back and cut the path we we’d come down. In short, we were surrounded. Suddenly, Pran looked not so happy. We both knew the tales of other journalists captured by the KR. Few emerged alive. “Oh, not to worry,” the captain continued brightly. “Give us a little while, and we’ll fight our way out.” This, of course, coming from the side that was engaged in a war they would ultimately, just a few weeks hence, lose—touching off a slaughter of holocaust proportions. We were at the mercy of a few hundred soldiers who seemed to be thinking more about their paychecks than the lives of an American reporter and his translator that seemed to hang in the balance.

But we had no choice. We waited. Lots more chatter on the radio. Finally, another hour passed. The path had been cleared; the colonel announced. “You’d best move quickly, though. And I’d stick to the path. They’re still out in the trees on both sides.”

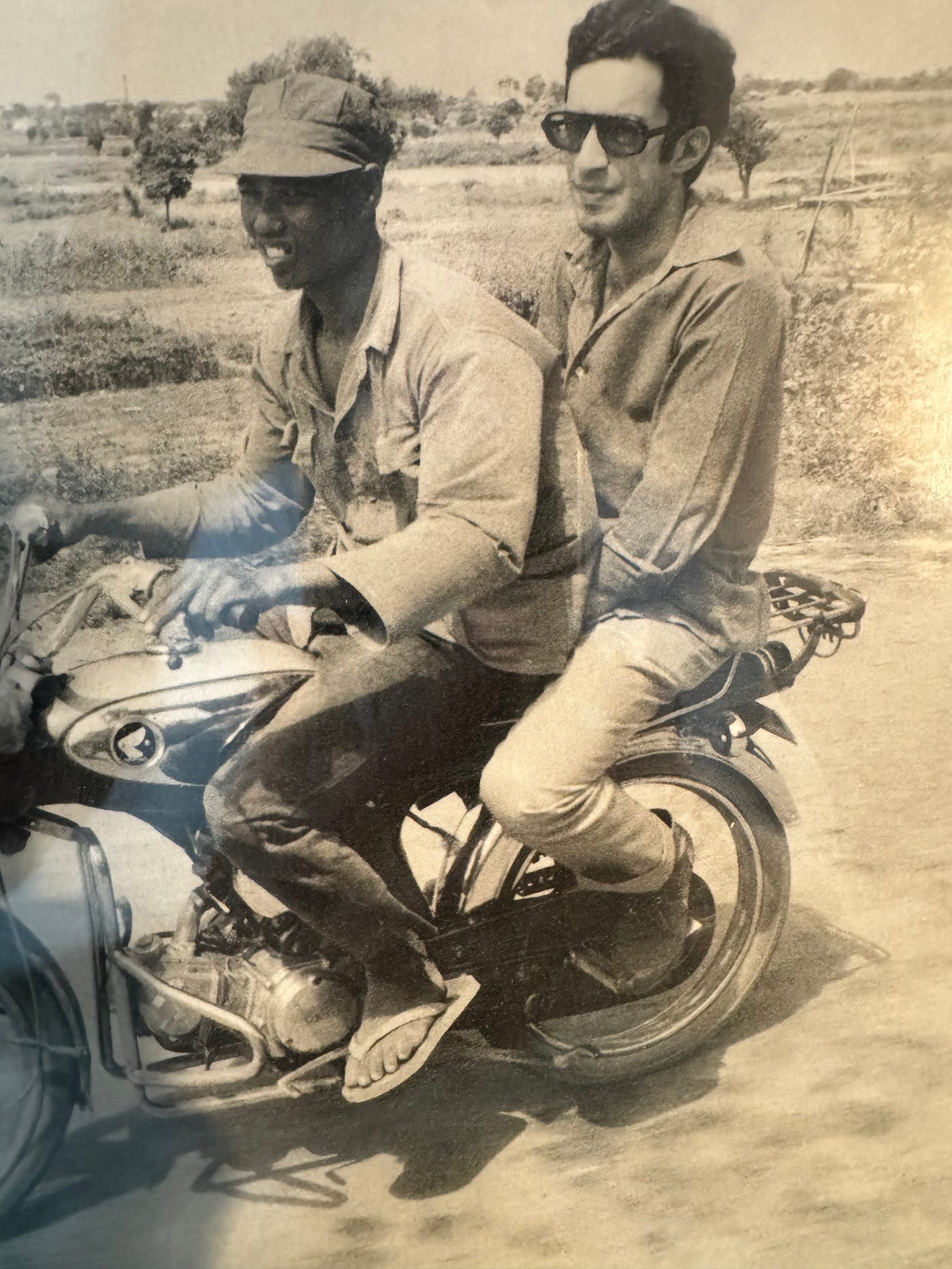

I suspect I never did a faster mile in my life. As we panted up to our motorbikes on Highway One, the drivers leaning lazily against them and the villagers still unconcerned, I recognized that I’d learned a first rule of war correspondence, the hard way. Always know where you’re going, and how to get back. Our narrow escape, though, never made it into the paper. The first rule of Abe Rosenthal—“readers don’t care how you got the story; they care about the story.” Okay, so now it can be told. I still have the photo Pran took of me, perched on the rear seat of the motorcycle next to mine as we headed back, both of us quite relieved at our apparently quite narrow escape, the hot wind blowing through my too-long hair (yes, I very much needed a haircut, but who had the time or the inclination?).

Photo by Dith Pran

To this day, I look at this photograph on my mantle in our living room, and each time, the same thought goes through my head as at the very moment Pran snapped it. However did I survive?

Throughout my little ordeal and many times afterwards, shivers ran up my spine as I thought of Kate Webb and how close I came to her experience or much worse. Kate was the correspondent for United Press International, at a time when that news agency was every bit the worthy competitor of the Associated Press. When I first met her, she was a stunning, but steely young woman—one of that rare breed of war correspondents in the Indochina theater including the likes of my Times colleague Gloria Emerson or photographer Sarah Webb Burrell. But there was something just a little bit off about Kate and it was only gradually that I was able to piece together her story. Of New Zealand-Aussie blood, at the age of twenty-four, Kate decided to pick up and head to Vietnam. Three years later, with the death of the UPI Phnom Penh bureau chief Frank Frosch, whose body, riddled with bullets, was found face-down in a rice paddy in southern Cambodia, victim of an insurgent ambush, and the ninth journalist murdered in the maquis, Kate was named to replace him, largely because of her ability to get by in French.

A year later, she was captured by North Vietnamese troops operating alongside their Khmer Rouge allies. On April 21, 1971, The Times, reacting to preliminary and fortunately erroneous reports, published her obituary. In fact, in many ways her saga was much worse. On April 7, 1971, accompanied only by her Cambodian driver, they’d been ambushed on a coastal road, when, as she wrote, “without warning the world exploded into the crack and whistle of small-arms fire, the crash of mortars and the sudden screams of wounded.” Racing into the jungle, she eventually ran straight into two North Vietnamese soldiers with AK-47s. Bound with wire, she was force-marched through the jungle until her feet turned to pulp. After a week, reaching a remote camp, the interrogations began. On May 1, as a gesture to the international celebration of Labor Day, she was suddenly released, stumbling out of the jungle, 22 pounds lighter (she was never what one could call zaftig), burning up with a 105 degree fever and infected with two strains of malaria that she never fully shook.

“People always think I must be so tough to survive all this,” she said later, “but I'm a real softie. But maybe that’s what it takes—you have to be soft to survive. Hard people shatter.” Kate never shattered, but then she was never quite the same again. Moreover, it was quite likely that her survival was indeed a tribute to her fortuitous capture by North Vietnamese main force troops rather than the Khmer Rouge. While many of these had been trained by Vietnamese, they were far more brutal, ruthless and unforgiving than their neighbors. To my knowledge, not a single journalist who fell into KR hands ever lived to tell about it. Their mutilated bodies, occasionally recovered in the jungle, told enough of the story.

Meanwhile, the war was continuing day by day to grind on, with an increasing tempo of Khmer Rouge victories, pushing the American-backed forces of President Lon Nol increasingly back to the wall, seizing new and strategically critical territory. Three days after my foray to the front, I had the off-lede story in Saturday’s Times.

Cambodian and Western (e.g. Americans who did not want to be identified) military sources were reporting that government troops had lost their last beachhead on the lower Mekong River—an entire garrison of 800 to 1,000 troops evacuated by navy craft up to the provincial capital of Neak Luong, which was itself not to be held for very long against a determined Khmer Rouge assault. The loss of that beachhead effectively closed off the Mekong as a resupply route at the same time rocket attacks intensified on Pochentong Airport, where I’d had to run for my life a couple of weeks earlier. When the U.S.-backed forces had fled their position on the Mekong, they’d left behind three large 105-mm howitzers and a large stock of ammunition. Indeed, one military attaché told me that the shells falling on Pochentong were found to have serial numbers indicating that they’d been captured since February 1. Increasingly, our own weapons and ammunition were being returned to us—with often deadly consequences.

Each morning, after Pran made his first pass by the PTT office, he’d bring the morning’s communications from New York that had arrived overnight by telex. Among the cables each day were the frontings, which in addition to conveying how our stories were played also contained a note on wire stories that were used when a correspondent was unable to file or not in a position or inclined to do so. The morning of March 11, Pran arrived dutifully with this flimsy sheet of telex paper, and I glanced at it, then leapt to my feet. For there, toward the bottom, was a small Associated Press story reporting on an attack by North Vietnamese forces on the tiny village deep in the Central Highlands of Vietnam. I controlled myself. No panic, I thought. Perhaps just a coincidence, but in a flash I was back in that small windowless conference room buried in CIA headquarters in Langley, Virginia. I decided to wait a day or so. Sure enough, the next morning came Jim Markham’s story—NVA troops had fired 400 heavy artillery rounds on the nearby provincial capital of Ban Me Thuot, then surrounded the town. Indeed, it was Jim Markham, who I was supposed to be replacing, who'd authored the piece.

“That’s it,” I shouted to Pran, then fired off an urgent message to the foreign desk. It’s all over, Vietnam is falling, I proclaimed chicken-little-style. The message that returned later that night was, at best patronizing. Not to worry, Gerry Gold, the stable, sensible anchor of the dayside desk, wrote back. Saigon will still be there when you arrive, and by the way your luggage got there today. Needless to say, I followed the progression of stories closely. Sure enough, just as predicted, North Vietnamese forces made quick work of Ban Me Thuot, sending thousands of refugees fleeing toward the coast, then turned south, the South Vietnamese army collapsing before their onslaught—the final push of the war to “liberate” their nation. Indeed, it all happened in precisely the order but an even more compressed timetable than my CIA briefer had suggested.

The Times had sent in reinforcements, especially Malcom W. Browne, the dean of the American journalists who’d covered Vietnam. In 1964, Mal, who who’d worked at the time for the Associated Press and was married to a lovely Vietnamese lady, had shared the Pulitzer Prize for International Reporting with David Halberstam of The Times for “their individual reporting of the Viet Nam war and the overthrow of the Diem regime.” Now, returning for the denouement, he had the five-column lead of the paper: “SAIGON REPORTED ABANDONING TWO-THIRDS OF SOUTH VIETNAM; QUANG TRI FALLS, HUE IN PERIL.” Nestled next to his story, also above-the-fold, was my own dispatch from Phnom Penh: “Cambodian Rebels Near Naval Base: Insurgents Break Through Government Lines Only 2 miles from Capital.” Clearly, everything was breaking simultaneously across Indochina. In Phnom Penh, the noose was closing in desperately close.

Ever since, I have had enormous respect for those quiet analysts who labor, often with little respect, in the halls of Langley. Certainly, they have made their mistakes, at times a trifle publicly. But all too frequently, I am persuaded they get little credit for their prescience that may go all but ignored by those who make policy through personal prejudices, conventional wisdom or some herd mentality. Clearly this was the case of my anonymous, and totally prescient briefer.

Meanwhile, one morning, I woke up ghastly, potentially deathly ill with what was clearly a raging fever, effluent emerging from both ends of my body at the same time. Recognizing that Schanberg would do little to help, I managed to drag myself down the hall to a potentially more sympathetic ear. H.D.S. (Dave) Greenway was the charming, handsome, patrician correspondent of our arch rival, The Washington Post. While a first-rate and most competitive journalist, he also had qualities that Schanberg lacked—a real humanity and sympathy for those who suffered, even among his fiercest competitors. Clearly, I was suffering. Greenway had only one suggestion and promptly proceeded to implement it. He dragged me (almost literally, since I could hardly stand), out of the hotel, across the road and into an old French-colonial style compound. It was serving as a hospital and after we’d picked our way across bodies lying on the floor, most of them in even worse shape than I, Dave deposited me in the office of a young French doctor. He took a brief look at me, pulled out a thermometer, which registered 105 degrees, and shook his head. I didn’t like that at all.

“I don’t know what you’ve got,” he said succinctly, then reached for a bottle on a shelf. “But take these. By tomorrow, you’ll either be better or you’ll be dead.” Nice. I staggered back to my room, swallowed the pills, collapsed on my bed, pulled the mosquito netting around me (probably too late, I reflected) and passed out. The next morning, I woke up in a state that approximated my young doctor’s first alternative. I was better. The fever had broken, I was no longer pumping out crud from every orifice. Forever after, I have credited young Greenway with saving my life. He, on the other hand, barely remembers. Just another day in the life of a foreign correspondent.

By now, my time in Phnom Penh was also drawing to a close. On April 5, I filed my final story, describing the grim conditions as refugees from the fighting around Phnom Penh were themselves again fleeing toward the city center. A week earlier, I’d been at the refugee camp on Route 5 about five miles northwest of the capital—a bustling community of some 10,000 people. On April 5, most having fled toward downtown, it was largely deserted when I swung through quickly on a motorbike. We turned rapidly back to town as small arms fire crackled through the camp from across the river where KR forces were also launching artillery shells and rockets that burst among the shanties. It all seemed like a bookend to my weeks in Cambodia—my arrival amid a rocket and artillery attack. Now I was being saluted with farewell salvos.

In their new location in the outskirts of the camp, I found Am Min, who had just moved for the fourth time ahead of insurgent advances. It had all begun last spring when the Khmer Rouge first entered her native village of Somrong on the same Route 5, but fifteen miles north of Phnom Penh. Her husband had died in fighting six years earlier and she was struggling to support her five children when she picked up and fled for the first time—four miles south to a new refugee camp at Tuol Sakor. Four months later, the war had reached her again, so again she was on the move, three miles closer to Phnom Penh at Phum Baset.

In January, she’d reached the spot where I found her just outside the city. “If they attack I will move again,” she told me, as her hands, constantly moving, continued to their mechanical work, weaving long dried reeds into mats on the wooden floor beneath her. “But someday I would like to go back to my own village if the war ends.”

For me, the war ended the next morning. Schanberg clearly wanted this story, especially its denouement, to himself. So, Sydney was delighted to facilitate my departure. And though the big airlifts of rice and ammunition had been largely suspended, Air America, the CIA-backed airline whose slogan was “Anything, Anywhere, Anytime, Professionally,” was still running the occasional two-engine prop Fairchild C-123 Provider into and out of Pochentong, bringing materiel and the occasional food in and ferrying people like me, out. I was told I could bring one suitcase only—so of course it was my precious canvas T. Anthony. At ten o’clock in the morning, I was out standing next to the taxiway as I saw the lumbering prop begin its falling leaf pattern. The instant it landed, the flight was surrounded by ground workers, offloading its slim cargo. They’ll keep the props turning, I was told, and you won’t have much time as I crouched in the tall grass and in the not very far distance shells were landing. “OK, run for it,” my escort said. Dragging my suitcase, I ran for the open rear cargo door, heaved the bag in and leaped in behind it. Seconds later, the pilot started the takeoff roll, and we were in the air. Down below, I could see puffs of smoke just beyond the runway we’d left. An hour or so later, we were touching down in Bangkok. My war, the shooting variety, was over.

Finally, on Saturday, April 12, after a couple of phone calls with Jim Greenfield in New York, the powers that be decided that it was really quite futile to send me into Saigon. “We’re trying to figure how we’re going to get the people we have in Saigon out at this point,” Greenfield observed. Instead, I was off to the Philippines and Clark Airbase where waves of refugees from Vietnam were beginning to arrive en masse by a major air bridge that had been opened between Tan Son Nhut Air Base in Saigon and Clark.

Next week, we'll pick up the story of the final days of Vietnam, through the prism of those fleeing for their lives.

So VERY kind, K. M. compensates (and more!) for all the work !!

Thanks ever so much, Elizabeth .... more than compensates for the 10 churlish subscribers who've promptly 'disabled' me after this !!