Unleashed Opinion: Economic security for a world (or nation) in crisis

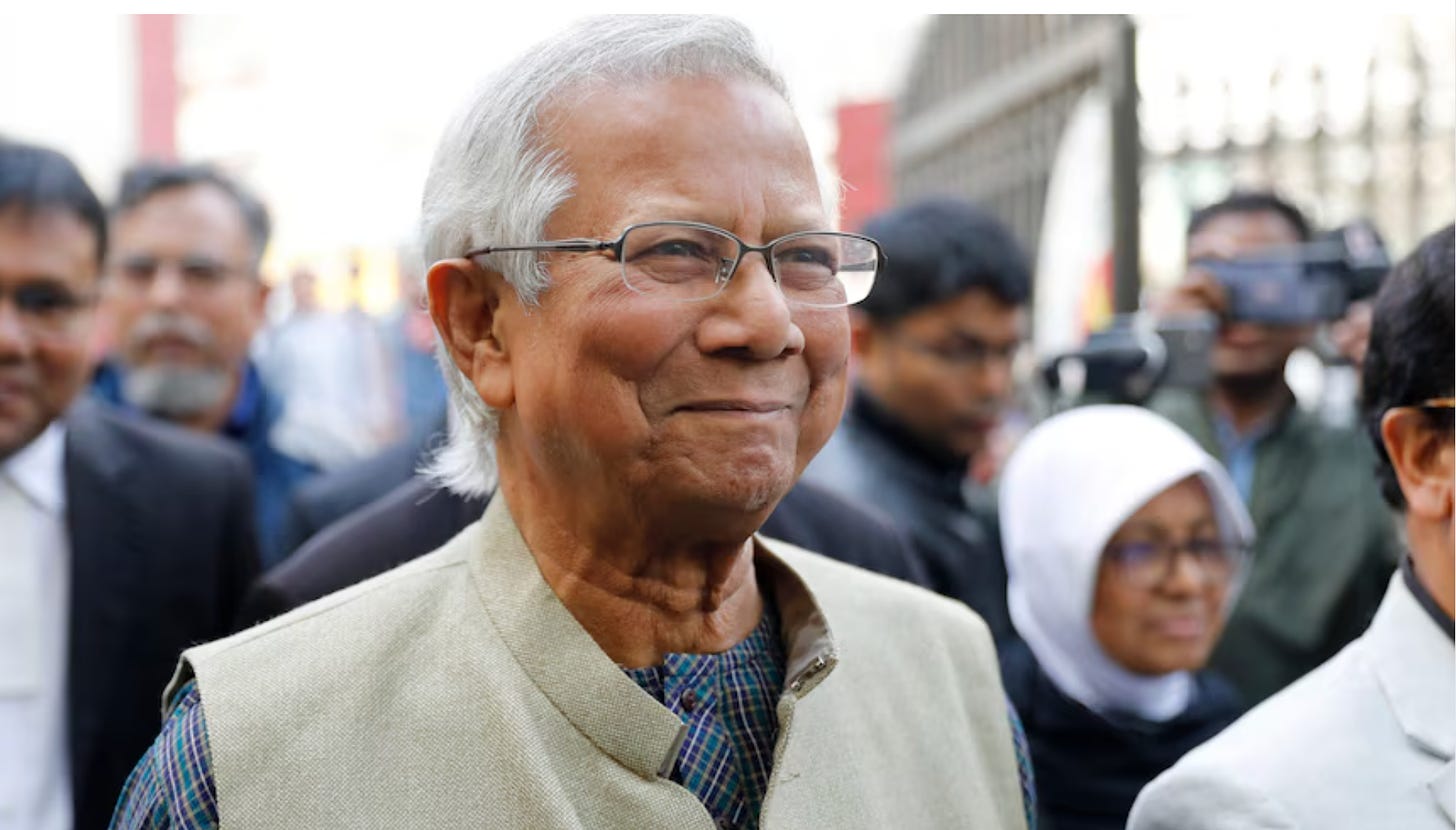

An opinion from Bangladesh Nobel Peace Prize winner Mohammed Yunus for his nation, in deep trouble, that he is now, suddenly leading

This is the debut of a new feature for Andelman Unleashed—Unleashed Opinion. And on the very day that CNN has chosen to put a stake through the heart of its CNN Opinion site, not to mention all those brilliant minds who wrote for it and the extraordinary editors who made them even greater, we embark on its successor—designed to give voice to the newly voiceless.

It is fitting that for our launch voice, we turn to Muhammad Yunus, founder and managing director of the Grameen Bank, who was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 2006 for developing the concept of microcredit as “an important instrument in the struggle against poverty.”

A true son of Bangladesh, much of his life’s work has been based there. This week, following a succession of riots that left hundreds dead, the nation’s 77-year-old Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina, who has ruled with an iron hand for more than 15 years, resigned and fled the country after hundreds of people were killed in a crackdown on demonstrations that began as protests against job quotas and swelled into a movement demanding her ouster.

Almost immediately, Yunus, one individual deeply respected by the broad mass of Bangladeshis, was asked to step in and help restore order from this lethal chaos. It is a tribute to his life dedicated to establishing an economic and social system in his nation—by far the world’s most densely populated—that is as fair and equal to the vast mass of the most deprived as it is to the privileged few.

This opinion is adapted from an essay, which I commissioned from Yunus for World Policy Journal in 2008. It is no less relevant in today’s deeply fractured Bangladesh.

By Muhammad Yunus

Capitalism is in serious crisis. Even so, no one is calling for it to be abandoned in favor of some other system, such as socialism, because everybody is convinced that, with all its faults, capitalism is still the best economic system known to humanity.

The need for reviewing the basic structure of capitalism has seemed appropriate on many occasions, but never so clearly as it is today. Indeed, in light of the current global economic crisis, there is strong support for a major overhaul of the system. In my view, one major change in the theoretical framework of capitalism is necessary—a change that will allow individuals to express themselves in multi-dimensional ways and address the problems left unsolved or even intensified by the existing conceptual framework.

In these early years of the 21st century, we were living in a time of unparalleled prosperity, fueled in part by revolutions in knowledge, science, and technology. This prosperity had dramatically improved the lives of many; yet billions of people still suffer from poverty, hunger, and disease. In the developed world, a handful of economists and social scientists have been clamoring to draw attention to their plight. Many people, however, took a complacent view, assuming that the spread of free markets would bring eventual prosperity even to the world’s poorest peoples—a long way toward the broader objective of greatly reducing the gulf between the rich nations of the global North and the poor nations of the global South. Many of us were convinced that the coming decades would bring unprecedented wealth and prosperity, not just for a few, but for all people on this planet.

Now the mood of optimism has changed. Several major crises that few people foresaw—the financial crisis, the ever-worsening environmental crisis, and crises over food and oil prices—have converged to bring even greater misery and frustration to the world’s bottom 3 billion people. And these crises have also driven many in the developed world to question the solidity of the foundations on which they had assumed their future security and prosperity were being built.

Drawing by Damien Glez / Burkina Faso

We are in for a long and painful period ahead. The combined effects of the financial, food, energy, and environmental crises will continue to unfold in the coming months and years, affecting the security of the bottom 3 billion with particular force. Social unrest, border clashes over scarce resources, increasing instances of state failure, and vast migrations by populations desperate for relief from poverty and environmental disaster will create political and military hot spots around the globe that will threaten world peace and strain the budgets of established and emerging powers struggling to cope with these challenges.

Yet, in the face of all this dire news, it is possible that this mega-crisis could be a mega-opportunity—to redesign our existing economic and financial systems so that they can become the foundations for lasting global security.

A family of companies, 25 in all, founded by Grameen Bank over decades in an attempt to address different problems faced by the poor in Bangladesh…

Even if we can overcome the immediate crises we face, we will still be left with fundamental questions about the effectiveness of capitalism in tackling such unresolved problems as persistent poverty, lack of access to health care and education, and epidemic diseases. In my view, the theoretical framework of capitalism that is widely accepted today is a half-built structure.

With this in mind, I have proposed a new type of business that would operate in the same market along with existing profit-maximizing enterprise. I call these new entities “social businesses,” because they exist for the collective benefit of others.

It is important to distinguish the concept of social business from the well-known idea of “socially-responsible business.” The latter refers to traditional for-profit companies that choose to modify their business activities so as to promote social goals, or, at least, to minimize the social harms they cause. Socially-responsible businesses may use environmentally-friendly methods, provide generous benefits to employees and their families, and donate a portion of their profits to worthwhile causes.

The concept of social business crystallized in my mind through my experience with Grameen—a family of companies, 25 in all, founded by Grameen Bank over decades in an attempt to address different problems faced by the poor in Bangladesh. These companies vary widely in their goals and business models. Grameen Shakti, for example, produces and sells low-cost, renewable energy systems, including solar panels and bio-gas converters that turn otherwise valueless farm wastes into cooking fuel. Grameen Health Care runs health clinics and provides affordable health insurance to rural families. Grameen Fisheries and Livestock operates fish farms and provides vaccination and veterinary services to help small farmers in Bangladesh improve profitability. Grameen Bank itself is a social business. Owned by poor people, mostly women, who are its depositors and borrowers, it pays part of its profits back to the owners in the form of dividends, and invests the rest in expanding its services to more villages and families throughout the country.

Thus, all the revenues that flow through Grameen Bank go to help the poor in one way or another. In each case, the companies address a specific social need.

We designed these businesses to be both self-sustaining and expanding, but only to ensure that the products or services they provide can reach more and more of the poor, on an ongoing basis. Any surpluses generated by these companies are re- invested to expand operations, rather than enrich investors. This is the model of a social business.

The concept of social business got international attention when Grameen Bank launched a joint venture with Danone, a multinational company headquartered in France. In February 2006, Grameen teamed up with Danone to bring nutritious fortified yogurt to the undernourished children of rural Bangladesh. The aim of this social business was to fill a nutritional gap in the diet of these children.

We began selling the yogurt to poor families at an affordable price, charging just enough to make the company self-sustaining. In the process, we stimulated the local economy, since the yogurt was distributed door-to-door by a small army of village women who earned a commission on each cup of yogurt they sold. Furthermore, all the milk and other ingredients in the yogurt are purchased from local suppliers, such as small dairy farmers in the vicinity of the factory. Beyond the return of the original investment capital, by agreement, neither Grameen nor Danone would ever make any money from this venture.

We also have built an eye-care hospital that operates along social business principles and a joint venture with Veolia of France to deliver safe drinking water in the villages of Bangladesh. This partnership is in the process of building a small water-treatment plant to bring clean water to 50,000 villagers in an area of Bangladesh where the existing water supply is highly contaminated with arsenic. We sell the water at a very affordable price solely to make the company sustainable, but no financial gain comes to Grameen or Veolia. The success of these first enterprises has encouraged other companies to come forward and partner with us to set up new social businesses.

There is no dearth of philanthropists in the world and no dearth of donor countries giving grants. People give away billions of dollars every year, as do donor countries. But imagine if, instead of those billions of dollars going to supply one-time aid, they could be used by social businesses to help people. The money would then be recycled again and again, and the social impact could be that much more powerful. In the same manner, money allocated by companies to corporate social responsibility projects could easily go into developing social businesses. Each company could create its own range of social businesses or pool donations from many sources in Social Business Funds (SBF), comparable to private equity pools that operate in the for-profit world.

The opportunities for launching social businesses are limitless. Even profit-maximizing companies can be social businesses when owned by the poor. This constitutes a second type of social business. Grameen Bank falls under this category of social business. It is owned by its poor borrowers. The borrowers buy Grameen Bank shares with their own money, and these shares cannot be transferred to non-borrowers. A committed professional team does the day-to-day running of the bank. Every year, dividend checks are sent to the borrowers, representing their share of the bank’s profits.

What I would like to propose here is that bilateral and multilateral donors support economic development by creating social businesses of this type. When a donor wants to give a loan or a grant to, say, build a bridge in a recipient country, it could create instead a bridge-building company owned by the local poor. A committed management company would be given the responsibility of running the company. Following the established model, part of the profits earned would go to the local poor as dividends, the remainder towards building more bridges. Indeed, that bridge would likely be the first of many. An array of infrastructure projects, such as roads, highways, airports, seaports, and utility companies, could be built in this manner. Because the social business model demands that the company generate ongoing revenues through its activities—for example, by charging tolls or usage fees on its bridges (usually with special lower rates for the poor)—the initial grant should lead to a continuing, ever-replenished revenue stream, ultimately producing more social bang for the donor’s buck.

Investors motivated by the desire to promote particular social goals would use this market to channel monies into social businesses that promote these ends. The values of shares in specific social businesses would rise and fall along with the results, both financial and social, of the underlying businesses. Social businesses that gain a reputation for producing powerful social benefits—operating schools for at-risk kids in poor neighborhoods, for example, or providing affordable, high-quality health care to families in low-income communities—while also generating strong, sustainable revenue flows through astute, creative management will become the equivalent of blue-chip stocks, attracting abundant investment money.

In a world where agricultural markets are global, the fate of a rice farmer in Bangladesh, a maize farmer in Mexico, and a corn farmer in Iowa are all intertwined. And while the past few decades may benefit a few at the expense of many others, in the long-run, only policies that will allow all the peoples of the world to share in the progress will produce long-term security for anyone.

Poverty does not belong in civilized society … instead in a museum

Poverty is not created by poor people; it is an artificial imposition on individuals and families with fewer resources than others. Poor people are endowed with the same unlimited potential for creativity and energy as any human being in any station of life, anywhere in the world. It is only a question of removing the barriers faced by the poor so that they can unleash their creativity and intelligence in the service of humanity. They can change their lives—if only we could give them the same opportunities that we have. Social business, and creative, sympathetic economic actors—across all sectors— are the quickest avenue to this end.

Poverty does not belong in civilized society. It belongs in a museum where our children and grandchildren will go to see what inhumanities people had to suffer, and where they will ask themselves how their ancestors allowed such a condition to persist for so long. We’ve accomplished so much thus far: eradicating diseases, outlawing slavery, raising crop yields dramatically. Eliminating poverty is our next great challenge. Now is the time to face these deeply linked global economic and social crises in a well-planned and well-managed fashion.

This is a unique historical moment. From the ashes a new society can be built, and the present crises allow us the opportunity to design and build a new economic and financial architecture so that this type of catastrophe will never recur. Only by achieving this can we lay a solid foundation for the security and peace of future generations.

Though this opinion was written in 2008, in so many respects it reflects on-the-ground realities today in Bangladesh. The moment it was being written saw Sheikh Hasina in the process of seizing power for a second, extended term. Time froze in Yunus’ nation. Now, perhaps there is the possibility of a new beginning and for the first time really with his hands directly on the tiller.

Andelman Unleashed will be watching.

Meanwhile, remember, for our paid subscribers, we’ll be discussing this and so much more on Friday on our weekly Unleashed Conversation. Do join us!

& somehow, Michele managed to avoid jailtime !

;-(((

Now there IS an idea.....a social business public transit .... that works for me !

I have a friend there who is an American entrepreneur who has also started ground-up businesses in Bangladesh ... I'll mention that!

thanks...and keep reading!!! (btw, if you are able, you should try a paid sub ... and join us for our Friday zoom !)