Unleashed Memoir #7 / Part II: On to Cambodia

1975 ... And the war begins .... but only for me !

On October 6, 2024, with my beloved wife of the past quarter century—Pamela—I celebrated the 80th anniversary of my presence on this planet among my fellow citizens of the world. As it happens, it also marked the half century (50 years) since I embarked on my life as a foreign correspondent, observer, and chronicler of more than 90 lands far from my own. To commemorate this, another moment from my own past, frozen in time, you will find here an excerpt from my memoir, "Don't Shoot, I'm an American Reporter,” which is still being written. From time to time, Unleashed Memoir will present excerpts from this work where and when they resonate especially. And in this excerpt, I am now embarking on the first of so many adventures to come.

Gerald Ford's just taken over as President from Richard Nixon … The world breathes a sigh of relief … But now for the debut of my first stint as a war correspondent, we pick up the story in the dining room of the Hotel Le Phnom in the heart of war-torn Cambodia. I’ve just arrived as February is bleeding into March of 1975 and there is a whole cast of characters….

Before I pick up the story, though, of what would become the last days of Cambodia as we knew it, let’s revisit a few of the intrepid souls I encountered from my earliest hours. Jon Swain of London's Sunday Times was by far the most brilliant, perhaps the most colorful, even the greatest journalist of them all. Thin, strikingly handsome, a large mop of light brown hair flopped disarmingly across his eyes graced with a perpetual twinkle that concealed the steel-trap mind hiding behind. Swain was every bit the prototypical, swashbuckling foreign correspondent.

His full name was John Anketell Brewer Swain, though I knew none of that until I began researching this book. Swain was of very much mixed parentage—English, Scotch, Irish, French and Spanish—and there was very much of each nationality embedded deep within his character. Not to mention his earlier life before he pitched up in Indochina. Expelled from the elite British prep school, Blundell’s, he promptly eloped to the French Foreign Legion. And later on, he’d variously be taken hostage for three months in Ethiopia, pinned down by hostile Indonesian troops on Timor and uncover a host of scandals while serving for years as The Sunday Times man in Paris. But at the time, Swain was at home in Cambodia, where he’d first arrived nearly five years earlier for Agence France-Presse (his French was impeccable), and served as one of several go-to guys for newly arriving tyro scribes like myself.

Also gathered around that table at breakfast my first morning was Bruce Palling who has remained a close friend through the years. Bruce, or as my wife Susan would later dub him, “Bruzie from the Home Office,” was every inch the pukha young English nob.

Bruce would wind up as my escort of choice throughout Southeast Asia over the next several years. With a demeanor similar to Swain’s, and his round owlish glances and sly grin, Bruce was reporter to the world. From the Times of London to the BBC, the Washington Post, The Guardian and a host of other “strings,” or freelance gigs that would come or go, heaven forbid that you got behind him at the telegraph office with only one circuit out of the country. It could be hours as Bruce would send off slightly divergent dispatches to each of his media destinations that were his daily bread (if not butter).

But Bruce also made it his business to know everyone—and persuade each of his impeccable sources that he was put on earth solely to entertain, edify and protect, so long as they provided him regular fodder of intelligence, color or simply a few bons mots. Eventually, Bruce would retire from journalism, at least as a profession, becoming a full time foodie, wine connoisseur and trader, custom travel professional and writer of food and wine columns for the European Wall Street Journal or The Guardian, among other outlets. But during my time in Asia, Bruce was every inch the foreign correspondent—Graham Greene style.

A Very Special Guest !

Andelman Unleashed has unleashed new, (lightly) paid tiers….For new paid subscribers, an inscribed copy of my latest book, A Red Line in the Sand…Along with a weekly portfolio of cartoons, largely from Cartooning for Peace … and Friday a weekly live conversation with Andelman.

THIS COMING FRIDAY, WE HAVE A SPECIAL GUEST:

Mort Rosenblum …

… has covered stories on seven continents since the 1960s, from war in Biafra to tango dancing by the Seine. He was the Editor of the International Herald Tribune in Paris; and then Associated Press chief international correspondent after running AP bureaus in Africa, Southeast Asia, Argentina, and France. He now runs Reporting Unlimited, which includes The Mort Report. He divides his time between a houseboat in Paris, an olive farm in Provence, and a succession of airplane seats.

So do upgrade here

… then you’ll get the zoom link to Andelman Unleashed Conversation … cheaper than a monthly mocha grande. Help us support great journalism across the globe.

Meanwhile back to the future … March 1975….

Then there were the photogs. Collectively and individually, each was in a class to him or herself. At the table that morning, and every morning, was Al Rockoff—one of the single oddest, most fearless and most supportive human beings I’ve ever encountered. If you were his friend, you were his friend for life and there was nothing he wouldn’t do to protect and befriend you. But he was most quixotic. Indeed, he had at least a dozen or so personalities and you never really knew which Rockoff was seated next to you when he plopped himself down. A large part of his often curious behavior he was wont to attribute to the steel plate in his head. He had apparently acquired this appurtenance when he was wounded by shrapnel during a Khmer Rouge attack on the strategic town of Kampong Chhnang, about 60 miles northwest of Phnom Penh, the previous October when it was still possible to venture that far out of town.

Demulder and LeRoy were two of the greatest women chroniclers of wars and conflict, but especially in Indochina. Rockoff especially enjoyed hanging out with both.

The KR had made lots of progress since then. Poor Rockoff technically died in that incident when his heart stopped, only to have it restarted by a Swedish Red Cross team. The wound in his skull was patched with the steel plate. Frankly I’m still not persuaded that it was the plate rather than the lack of blood supply to his brain that led to his bizarre personality, that actually endeared him immensely to the vast bulk of his comrades. I should add that he was quite a gifted, not to mention fearless, photographer. As were quite a number of others—the best of whom boasted that indispensable trait common to all great war photographers. Each was utterly without fear. Unlike a scribe who works with words, the photographer has nothing if he doesn’t get right up close and personal to the actual action. Quite simply, you have to be there when the shells land, the bullets fly, men, women and children are wounded or dying, all taking place hopefully just far enough from you that you can still trip the shutter and get away somewhat intact. Rockoff was one of those men.

Another was Phillip Jones Griffiths. Phillip was one of those individuals who didn’t just live an extraordinary life, he seized it, wrestled it to the ground, dug his teeth into it, and then of course he photographed it. A Welshman born and bred, he had been chronicling wars for fifteen years, nearly ten of them in and out of Indochina, but quite continuously in Cambodia since 1973.

In 1966, when he first pitched up in Vietnam, he began shooting for Magnum, the great global agency that represented such brilliant photographers as Henri-Cartier Bresson, Cornell and Robert Capa, and Tim Hetherington, another dear friend I would first encounter decades later, too short a time before he bled to death on the battlefields of Libya. Eventually, in 1980, Phillip would move to New York to assume the presidency of Magnum, a post he would hold for an unprecedented five years—while I was traveling the world for CBS News out of my base in Paris. But in 1975, Phillip was busily shooting the demise of Cambodia and the takeover by the Khmer Rouge. A big bear of a man, Phillip, like most of the great photographers, was both a loner and a boon companion. He would often say that he was especially “attracted by human foolishness,” but at the same time, “believed in human dignity and the capacity for improvement.”

Finally, there was Denis Cameron. Forty-seven years old, by the time I first stumbled upon him, Denis was really one of the grand old men of the Phnom Penh press corps. The ubiquitous, rangefinder Leica seemed grafted around his neck. He’d already passed through two ordinary lifetimes before I stumbled upon him.

Denis Cameron with the immortal Gloria Emerson, a dear friend from The New York Times…. —photo by Richard Avedon

But above all, Denis did not suffer fools gladly. Shortly after I arrived in country, a young NBC woman pitched up as part of the network’s new camera crew. She was the sound woman in the days when a crew consisted of a cameraperson, soundperson, producer and correspondent. As green as they come, a small, scared bird, she wore everywhere—breakfast, lunch, the field, to bed probably—her bullet proof vest and heavy metal military helmet, since someone back home, likely as a joke, told her under no circumstance ever to take them off in a war zone. This in a profession, at least in those days of innocence, where most of the cowboy photogs went into battle with, at most, a lightweight tropical vest to carry their spare lenses and film cannisters. Denis rose to the occasion and staged a Saturday evening party “welcoming” the new arrivals (aimed squarely at this young lady) on the second floor of a bistro that opened onto the central square where the PTT was located. He’d baked a large slab of chocolate brownies laced with hash, an attribute he pointedly omitted when touting their scrumptiousness to the young sound lady who promptly tucked into them, with no thought of the consequences. Within an hour or so, she was feeling quite good. Indeed, so good that sometime during the evening she managed to launch herself out of the window onto the plaza below. Fortunately, she suffered little beyond some cuts and bruises, but had little to do with Cameron ever after.

My most immediate concern, however, was with Schanberg and especially with his amanuensis, fixer, translator and soul mate to both of us. This was Dith Pran. Born in Siem Reap just outside Angkor Wat on September 27, 1942, he was almost exactly two years older than I was, but in terms of our understanding of his surroundings, we were light years apart.

Pran, a gifted photographer, was equally accomplished as a journalist, with a deep and penetrating understanding of people and society, but especially of Cambodia. His sole misjudgment, though, was an acute one. Like so many of his peers who I would come across during my few weeks in their country and the years I spent talking with them in refugee camps across the Thai border, they believed before the communist victory, that it was the war, not the Khmer Rouge nor the American-backed forces of Lon Nol, who were their nation’s deepest problem. “We are all Khmers,” Pran would tell me on no end of occasions, especially when I expressed my growing concerns about the potential barbarity of the KR. “All we need is for the war to end, and we can all live together again in peace and rebuild our nation.” How wrong he would turn out to be.

Still, for the time I would pass in Cambodia, Pran was my guardian angel, interpreter, the prism through which I saw his country and the terrible traumas through which it was passing in the final weeks of a war that had gone on far too long. At least, he served these functions whenever I could pry him from the cold hands of Schanberg. Pran learned French in grade school, then taught himself English, in which he was quite fluent. He was a sponge for any new colloquialisms we would spring on him. By 1972, when the Khmer Rouge insurgency had engulfed the country, Pran brought his family to Phnom Penh, and Schanberg, newly arrived in the country from his base in Singapore, had latched onto him. They’d been joined at the hip ever since.

As for Schanberg, well he felt, with some justification, that he owned the story of the decline and fall of the Cambodian empire. Sydney Hillel Schanberg was born on January 17, 1934, so at the time I arrived in Phnom Penh he had just turned forty. He’d begun his career at The Times as one of Sammy Solovitz’s copyboys. Sammy always considered him one of “his great successes.” His trajectory then paralleled mine to a degree—metro desk, a brief stint on national, then off to New Delhi just as I was arriving in New York as news assistant to foreign editor Seymour Topping.

In 1971, Schanberg covered the war between India and Pakistan, counting on his myriad stories of that conflict to win him the Pulitzer Prize. When the prize went to The Wall Street Journal’s Peter Kann, Schanberg, furious and devastated, made a quiet vow that the next conflict would be his, at any cost. And that cost would be heavy for just about everyone in Schanberg’s orbit. From 1972 onward, when Schanberg first arrived in Cambodia, he’d parked his family in Singapore and, though titularly the Southeast Asian bureau chief of The Times—the post I would assume at the end of the war—gave thought to little in that vast and tumultuous region beyond Cambodia. Now, with a new and untested colleague, your humble servant, at his side, Schanberg needed to get me up to speed quickly to do the daily stories that were the meat-and-potatoes of a daily like The Times, while at the same time making sure that nothing I produced could challenge his sole ownership of the Pulitzer he saw as his divine right.

And so, this education of a war correspondent began. At the time, of course, I understood little of the sub-text. I only thought it mildly rude and embarrassing—to both of us—when Schanberg would barge into an embassy briefing with a few of the leading American newspapers and agencies and order me out of my seat so that he could assume his rightful place. Or when he monopolized Pran and foisted a decidedly second-rate translator on me for a story that would clearly be the paper’s front-page lead that night. But, I reasoned, I was indeed here just as Schanberg’s sidekick—a minor detour before heading for the “real” story in Saigon for which I’d so long prepared.

Indeed, I had much to learn. Phnom Penh itself was quite a fascinating corner of the universe. A unique amalgam of French colonial architecture and city planning grafted onto a Southeast Asian provincial capital, the French influence was still a very real presence. Each afternoon, a small gaggle of French rubber planters would gather around the pool in the Hotel Phnom and speculate on life after the Khmer Rouge—how their plantations, essential to the economy of this nation, would suddenly acquire new value and they would be welcomed back to their properties by the nation’s new rulers to “teach” them how to operate their birthright.

They seemed all but oblivious to what the reality that awaited them. Herded summarily out of this country where many had spent their entire lives, with little more than the shirts on their back and a small suitcase of belongings—a bitter and tragic end to a lifetime dedicated to lost and stolen dreams—they would be lucky to have escaped with their lives.

Phnom Penh itself consisted of a collection two- and three-story buildings with the occasion four or five story structure towering over them, all in the same cream-colored stucco, many with ornate colonnade terraces and balconies, looking down on broad avenues.

These were often clogged with cyclos—the three-wheeled pedicabs that could bear one or two passengers beneath a canvas canopy sheltering from the intense sun or beating rain while the Khmer owner-driver pedaled frantically behind. The open-air stalls of Cambodian peasants, many with produce brought that morning from the countryside, operated cheek by jowl with small shops, often owned by the overseas Chinese community who were the more affluent merchants.

A clutch of embassies remained in operation—dominated by the French, which looked after the interests of a host of relief workers and agencies. At the American embassy, ambassador John Gunther Dean and especially his military attachés continued to call in air strikes by American warplanes on targets out in the countryside. These activities made the ambassador’s briefings somewhat valuable for the intelligence he was receiving from military forces out on the front lines. Dean was a veteran of Indochina, having served at one point or other in his career in all three nations—Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia. Beginning in 1953, at age 27, Dean arrived as assistant economic commissioner with the International Cooperation Administration in French Indochina, bouncing between all three capitals—Saigon, Vientiane and Phnom Penh.

With that kind of early background, it was not surprising that he was assigned to Paris in 1965 and played a significant role in helping convene the four-cornered talks between North and South Vietnam, the Viet Cong and the United States that opened in 1968.

Dean’s first ambassadorial post was in Phnom Penh, arriving in March 1974 fresh from a two-year stint as chargé in Vientiane. There he’d played a behind-the-scenes role in establishing a coalition government including some Pathet Lao (communist) members that delayed their immediate takeover. In retrospect, of course, this was only a brief delay of the inevitable. By the time he arrived in Cambodia, though, that war had effectively been lost—and to an enemy far more vicious than even the most fevered imaginings of the Pathet Lao. No velvet-revolution coalition here. Cambodia and the Khmer Rouge were quite a different story than Laos, as I would find out soon enough. On April 12, 1975, bearing the neatly-folded flag that hung over the embassy, Dean went out on a group of Marine helicopters, five days ahead of the Khmer Rouge arrival in the capital—leaving behind a handful of American hacks, but taking with him every American who wanted out.

Dean’s relationship with The Times was basically a need-hate. He needed The Times for its unparalleled direct line to those who were making decisions in Washington and other capitals around the world. He hated us, personally, for filing the kind of stories that made it so much more difficult to paint a picture of a regime Washington needed to love. Still, when a front page story of mine that all incoming American flights had been suspended caused the Pentagon to order their resumption, that was a golden moment for all of us. With respect to The Times’s main Man in Cambodia, Sydney Schanberg, it was more of a mutually symbiotic relationship. If Dean needed Schanberg for his pipeline onto the front page of the world’s Newspaper of Record, Sydney needed Dean for the scoops he was capable of doling out. And he guarded that relationship jealously.

I found Dean a brilliant but somewhat arch member of a diplomatic corps that still believed it had a significant role to play in nations where its members were posted. Most days, there would be a briefing, generally by Dean himself, a public affairs officer or military attaché, usually on deep background (“diplomatic sources” or “western diplomats”) that would comprise anything from a paragraph or two in a roundup we were preparing or a page one lede. But most of those briefings were Schanberg’s turf as I discovered much to my chagrin. One of my first mornings prowling around the embassy, the public affairs officer snagged me and announced there’d be a briefing in a quarter hour and that he couldn’t find Schanberg—in those unimaginably distant days before cell phones or even pagers—so might I care to sit in? I would. Big mistake.

Twenty-five years later, Jacques Leslie, The Los Angeles Times distinguished Indochina correspondent still recalled Schanberg in general and that moment in particular as vividly as I:

Schanberg was in a ferocious mood most of the time. The man considered most likely to emerge from the ashes of the Cambodian war with a Pulitzer, he perhaps had more reason to regret Vietnam’s emergence as a rival story than the rest of them. In addition, he couldn’t have been pleased that the New York Times sent…David Andelman [who] was new to both Indochina and foreign correspondence. Schanberg reserved his wrath for Andelman. He denounced Andelman to the rest of us [something of which I had no idea until I heard this decades later from Leslie, but today hardly, surprises me one jot], and strove to shut him out of coverage. It was startling to see Schanberg using up so much emotion on him, for he was no threat to Schanberg. Andelman appeared gaunt [indeed!] under his fresh safari suit [thanks, Susan!] and thick, black-rimmed glasses….Backing up Schanberg hadn’t been Andelman’s idea; he was supposed to be stationed in Saigon, but when the Lon Nol regime began to totter, he was diverted to Phnom Penh….

Soon after I arrived, I attended a U.S. embassy briefing at which Andelman represented the New York Times. That fact didn’t seem notable until a few minutes into the briefing, when the embassy press attaché interrupted to say he’d just spoken to Schanberg on the phone, and Schanberg wanted Andelman to leave the room immediately. We surmised that the attaché had informed Andelman of the briefing but not Schanberg; either Andelman kept the information to himself [wrong!] or wasn’t able to notify [or even locate!] Schanberg in time. Now Andelman slunk out of the briefing room, humiliated. Several minutes later Schanberg appeared. The briefing didn’t recover. Schanberg was as manic as if he’d been taking uppers: he dominated the briefing, virtually took it over. He asked questions and then answered them before the briefer had a chance, and rephrased other journalists’ questions instead of letting the briefer respond. The session ended desultorily once we had grown tired of listening to Schanberg interview himself.

Jacques Leslie/working —Photo by David Elliott

Jacques, a Yalie, indeed a graduate of the venerable Yale Daily News, who, much later in life, became a great and valued friend, may have stretched matters a smidge in singling me out as Schanberg’s particular target. Sidney was pretty hard on just about anyone who came anywhere in his field of fire. As it happens, I strongly suspect that the briefer was secretly delighted I was in the room instead of Schanberg. That way, at least there was a chance he might actually be able to impart some useful information to a group of real reporters, prepared to listen and learn.

I made the usual rounds of the various embassies, clearly aware that it would take far more than a brief visit from someone who was clearly little more than a transient visiting fireman to pry loose any remarkable new details of a war that had been covered for years by seasoned pros. Still, I had behind me the power and the glory of The New York Times, not to mention the International Herald Tribune, which appeared on the doorsteps of foreign ministries and prime ministers in their home capitals each morning, setting a global agenda of which I was now very much an intimate part.

Pran, the third permanent member of our merry little band, of course, had none of this access. But he brought far more to the table. Put simply, he knew how the wheels turned—who held the real reins of power, what people were thinking and feeling. In short, he brought a real sense of the texture of the country and its people to which few other correspondents were privy. And on more occasions than is even imaginable, he saved not only our careers, but our very lives. Neither Schanberg nor I took this at all for granted. But for all Schanberg’s professed love for this amazing man, he did not always treat Pran, behind closed doors, the way he ought to have been treated. Then again, Schanberg didn’t treat anyone else much better I guess. One morning, as I was quaffing down my orange fanta and protein-enriched roll, a newly-arrived British hack sat down with me and leaned over confidentially. “I say, there,” he smiled thinly, “was that you that Schanberg was laying into rather loudly sometime after three o’clock this morning?” I sighed. Nope, not me. I was sound asleep beneath my mosquito netting. I suspect that was Pran, I replied. “Poor bugger,” the Brit said sadly. Indeed, every now and then, Schanberg would outright fire Pran in the wee hours, and I’d have to hire him back first thing so we could go to work again.

I filed my first story just three days after my arrival. “Frightened Chinese Shut Most of Phnom Penh’s Shops,” read the four column headline on page three of that Saturday’s paper:

The heavy steel grates of Phnom Penh’s shops have been locked and barred for the last week. The stalls in the central market are deserted at what should be the afternoon rush hour. There is fear in the Chinese community and the economic heartbeat of this isolated city of two million people has come to a virtual halt…..

This fear of looting, vandalism, even violence against the ethnic Chinese by roving bands of Cambodian high school and colleges students has caused the shutdown of more than 90 percent of the estimated 6,000 Chinese shops and 10,000 market stalls that are the lifeblood of this capital city.

For the last two decades the Chinese have controlled Cambodia’s monetary economy and now they are being blamed for the sharply rising food prices, the inflation that is leaving Cambodians without enough to eat.

Inflation was indeed a daily reality—for we journos as well as our Khmer colleagues and all those with whom we came in contact. U.S. dollars—generally in the form of $100 bills, were exchanged all but daily on the black market, that had really become the only market. I’d “pigeoned” in several thousand dollars' worth of the long green, which Pran, or more often our driver, would exchange for the local currency—rials or the short pink, as we called it, a reference to the color of the by then all but worthless Cambodian currency. On the day we would have to settle up our hotel accounts, our driver would appear with large shopping bags filled with bricks—stacks of thousand and five thousand rial notes that were never undone.

Each stack was worth just a dollar or two, and we’d pile them in huge stacks on the front desk of the hotel as their cashier would solemnly count them up. And each time it would take a few more stacks as inflation continued to soar to Weimar Republic levels—only instead of overprinting their banknotes, they simply bundled them into bricks and pressed on. The entire economy, it seemed, was balanced on two legs of a stool—American aid which continued to pour into the federal treasury and vast quantities of rice, airlifted in on a constant parade of cargo flights by several relief organizations, particularly Care, and two Christian missionary groups—Catholic Relief Services and World Vision, though by the time I’d arrived there was little missionary work, since basic survival had taken precedence over the saving of any souls. In 1972, when the war really cranked up, the rice harvest was barely 26% of the figure just three years earlier, and in the final weeks of the war, barely any land at all was under cultivation and accessible to whatever population was still controlled by the American-backed government.

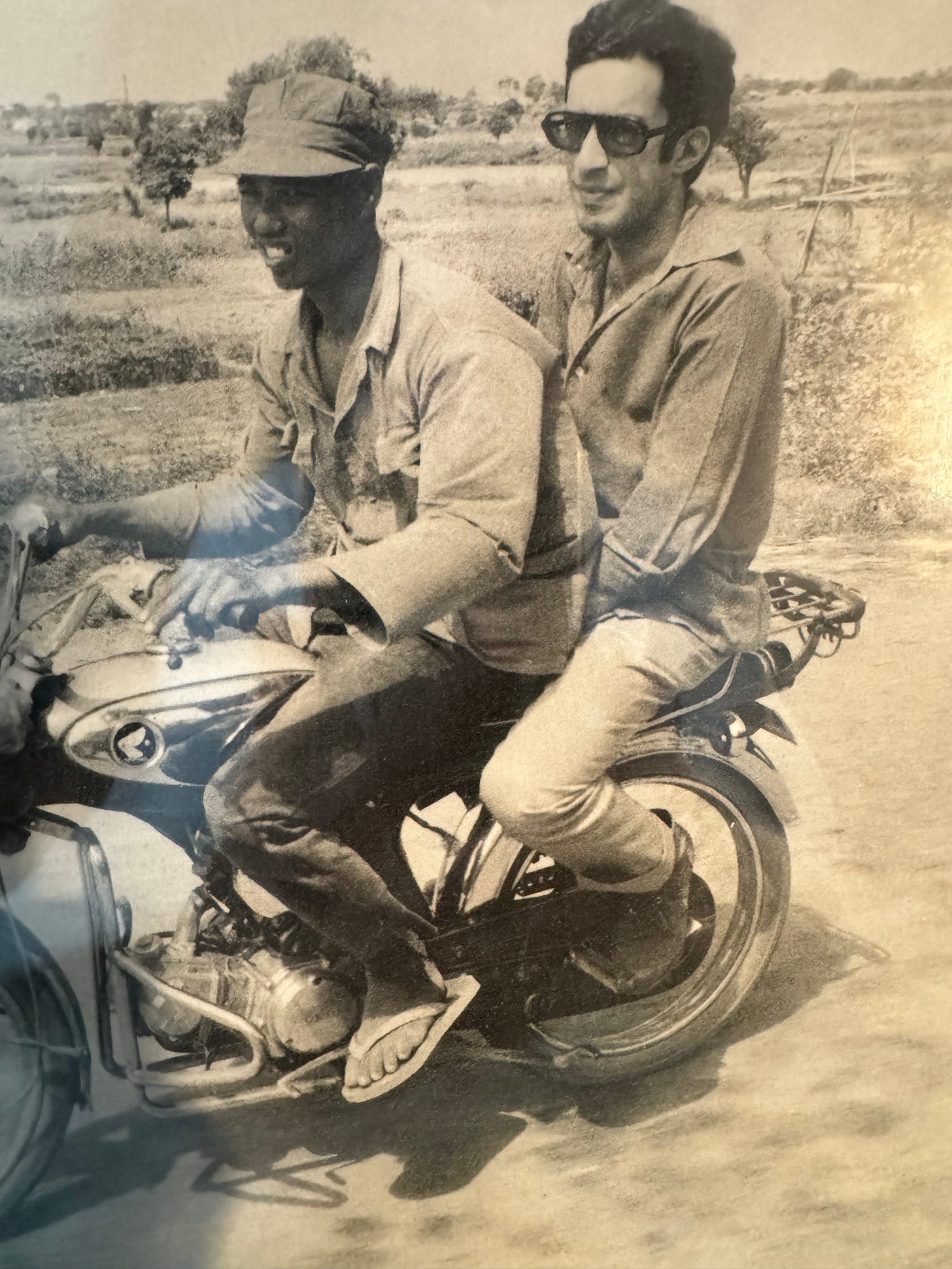

On March 5, 1975, Schanberg decided that it was time for me to visit “the front,” so he agreed to relinquish Pran for a day. And that nearly cost both of us our lives.

Stay tuned for Unleashed Memoir 8

Contact the International Criminal Court at: https://www.icc-cpi.int/about/otp/otp-contact

We have two very rich and powerful men in the United States who have closed USAID. It does not matter what party they affiliate with. As a result, thousands upon thousands of humans are dying around the world because they no longer can receive their medications for HIV or for TB. Women are again dying in childbirth - something that was eradicated up until January 20, 2025. These deaths ARE PREVENTABLE and are classified as "crimes against humanity." You can file a report anonymously with the International Criminal Court in Helsinki. The link is: https://www.icc-cpi.int/about/otp/otp-contact.

Your book will be captivating to read. I remember The Quiet American by G. Green and his irony to the American character.