Unleashed Memoir #7 / Part I: To Paris & beyond

Arriving in Paris en route to Saigon, it's 1975 … I'm rerouted…and adventures begin

On October 6, 2024, with my beloved wife of the past quarter century—Pamela—I celebrated the 80th anniversary of my presence on this planet among my fellow citizens of the world. As it happens, it also marked the half century (50 years) since I embarked on my life as a foreign correspondent, observer, and chronicler of more than 90 lands far from my own. To commemorate this, another moment from my own past, frozen in time, you will find here an excerpt from my memoir, "Don't Shoot, I'm an American Reporter,” which is still being written. From time to time, Unleashed Memoir will present excerpts from this work where and when they resonate especially. And in this excerpt, I am now embarking on the first of so many adventures to come.

Gerald Ford's just taken over as President from Richard Nixon … America and the world breathed a sigh of relief for just a moment … Now for the best part of my journey so far … I arrive in Paris en route to my posting in Saigon … but with a little detour in store.

When I checked in at The New York Times Paris bureau on the rue Scribe, I found a message waiting for me from Jim Greenfield, the foreign editor:

Stop off in Phnom Penh en route Saigon. Spend a few days with Schanberg. Get the lay of the land. You may need to spell him at some point.

Well, why not? I’d had the foresight to snag my visa for Cambodia in Washington. I had my green Air Travel Card, so it was simply a matter of re-booking to Phnom Penh instead of Saigon. True, I had no small amount of luggage—after all, I was moving to Saigon, wasn’t I? But as I hung around the Paris bureau, another message dropped, this time from Sydney Schanberg himself. Clearly news traveled fast, even in those days:

Heard you were stopping by on your way out. Pick up as many tinned goods as you can carry—we never know when food might run out here. Need to be prepared.

Nice. Times Paris correspondent John Hess suggested that was pretty much carte blanche to go on a lovely shopping spree. So that afternoon, I picked up a dark gray Delsey, hard-shell suitcase, which would eventually be left for some Khmer Rouge colonel. Then, I took a trip to Fauchon, the world's greatest food emporium on the Place de la Madeleine, and loaded up.

Every kind of tinned food you could imagine—foie gras, naturellement, but a whole host of more basics, all carefully preserved in the gold and black signature cans that so marked Fauchon’s products.

I carted it all back to the hotel and packed it up. Thank heavens this was one of the first wheeled suitcases, since it felt like it was nailed to the ground it was so heavy. Hopefully it was the tins, not the food within.

An Exciting Visitor … For paid subscribers to Andelman Unleashed our Friday live conversation.

THIS COMING FRIDAY, WE HAVE A SPECIAL GUEST:

Mikhail Zygar, founding editor of Dozhd [TV Rain], the extraordinary independent and now defunct Russian television network. Now in enforced exile in the USA, Mikhail, with the greatest sources close to Vladimir Putin, is the author of a multiplicity of remarkable books as well as his own landmark SubStack page, The Last Pioneer …. So DO upgrade here:

… then you’ll get the zoom link to Andelman Unleashed Conversation … cheaper than a monthly mocha grande. And help us support great journalism across the globe.

After my little Fauchon idyll, I went about my business. Paris was one of the few cities in the western world where I could find representatives of the North Vietnam and Viet Cong (aka National Liberation Front) to talk with first-hand. And, representing the paper that had already dispatched one of its senior editors, Harrison Salisbury, to hear their “side” of the story in Hanoi, it was not difficult for me to get into the North Vietnamese mission on the rue Le Verrier in the 6th arrondissement, where Phanh Huy Thanh received me for more than an hour. On Friday morning, Thao Theari, of the Viet Cong saw me in their mission to Paris. The Khmer Rouge eluded me, however. Still, at that very moment, en route to my primary destination of Saigon, Cambodia seemed very much a sideshow—a perspective I eventually came to regret.

Later on Friday, I spent the morning with perhaps the single most compelling individual of all my pre-arrival briefings. Jacques Decornoy was an extraordinary figure of the French media-foreign policy establishment.

Trained at the L’Institut des Sciences Politiques, then finished at École Nationale d’Administration (the ENA), Decornoy was the antithesis of the prototypical énarque—who, among the several dozen of the chosen, the entitled ones, would immediately on matriculation assume their places atop the pinnacle of power of the French establishment. The top four or five in the class each year would be anointed “inspectors des finances,” since 1816 the rulers of the powerful French bureaucracy, overseeing every key ministry of the republic. A subset of these would go on to become president or prime minister of France, ministers of foreign affairs or the treasury, even rulers of Europe as eventual leaders of the European Union or its central bank. Other enarques would become French ambassadors, captains of industry or banking.

But Decornoy wanted none of this. Shunning the traditional paths to power, in 1964 at the age of 27, Decornoy joined the foreign staff of Le Monde, effectively The New York Times of the francophone world. Ten years later, he’d risen to the post of editor for Southeast Asia, a region that served as a potent element of the French national conscience, especially in the years after France’s catastrophic defeat at the Battle of Dine Biên Phu. Moreover, it turned out, Decornoy and by extension Le Monde had embraced many of the same revolutionary forces that had so embarrassed French forces, and subsequently a far larger and more committed force of Americans.

All this I knew before I stumbled into his office. What I was not prepared for, was the background—the reason for Decornoy's extraordinary embrace of what would become a charnel house administered by the brutality of the Khmer Rouge. It seems that one of his classmates at Sciences-Po, through which he'd passed en route to the ÉNA, had been a young Khmer student named Khieu Sampan—soon to be labeled as one of the bloodiest masterminds of Khmer Rouge Cambodia. Once we’d exchanged pleasantries as one young (Decornoy was barely seven years older than I at the time) journalist to another, he picked up a large manuscript from his desk and brandished it at me. “This is the thesis of Khieu Samphan,” he began. It had been written in satisfaction of the requirements of a degree from Sciences-Po more than a decade earlier. Decornoy, clearly quite taken by the document, launched into a summary. It outlined the creation of an idyllic Khmer state—a pastoral, Rousseau-esque nation where farmers would labor all day in the fields for the common good; where poverty, inequality and injustice would disappear along with all the evils attendant to an urban lifestyle of profligacy and greed. This end would justify any means to achieve it. Effectively, it was a blueprint for what Cambodia would become. Shortly after he wrote this, Khieu Samphan disappeared back into the maquis—the jungles and paddies of Cambodia—to take up arms as a leader of the Khmer Rouge.

It quickly became clear to me that Decornoy was prepared to overlook quite a lot in the interest of achieving this idyllic, pastoral paradise—at least from his perspective in a comfortable office on the editorial floor of Le Monde. As Decornoy himself wrote on July 18, 1975 :

Ce peuple est à l'ouvrage jour et nuit, si l'on en croit Radio-Phnom-Pen—qu'il n'y a aucune raison de ne pas croire en ce domaine—tout le monde vit de la même façon, transporte, pioche, reconstruit, repique, ensemence, récolte, irrigue, depuis les enfants jusqu'aux vieillards. L'allégresse révolutionnaire a, parait-il, transformé le paysage humain….Une société nouvelle est assurément en gestation dans le royaume révolutionnaire.

[ These people are at work, day and night, if one believes Radio Phnom Pen—there is no reason not to believe in this respect—everyone lives the same way, in terms of transport, pickaxe, rebuilding, transplanting, seeding, harvesting, irrigating, from children to the elderly. The revolutionary joy, it seems, has transformed the human landscape....A new society is certainly being born in this revolutionary kingdom. ]

Decornoy was very much part of a long tradition of French advocacy journalists—who considered their role not merely to chronicle, or even interpret, events, but to influence them. Basically, politiciens manqués, they sought to use the power and privilege of their position from the sidelines to influence the way their nation thought, and the leaders acted. Often, it was a position that covered them with a glory that few of their American peers, at least at that time, could even imagine. All too often, they bet on a losing horse. Today, of course, all too many American journalists, too, have taken on this coloration of participants rather than observers. We, and our society, I am persuaded, are the poorer—certainly the more polarized—for it.

Still, Decornoy’s motivations puzzled me for years, until his colleague Patrice de Beer helped peel back some of this mystery years later. I would meet Patrice in just a few days, not long after my arrival in Phnom Penh. If Decornoy was the soul of Le Monde in Indochina, Patrice was the paper’s eyes and ears—an extraordinary reporter with sources, especially out in the maquis that most of us only dreamed of. As I began writing these words, I asked him to reflect back on his editor, who would die of cancer in 1996 at the age of 59.

I don't know the background of the 1960s well enough, as I was then a student before spending two years in the French Embassy in Malaysia and joining Le Monde in 1970. At that time, any journalist—or scholar—working on Asia and on the Vietnam war had to have connections with the Paris representatives of the Indochinese revolutions—Vietnamese, Khmer and Laotian. Everyone believed they were fighting under Hanoi’s guidance. As you will probably remember, there was a strong empathy in French, American and other universities in the West for the Vietnamese revolutionary movement and against the American war policy in Indochina, culminating in 1968 with the May movement and the Tet offensive. It was not until 1976-77 that people started to realize there was a split between the Khmer Rouge and Hanoi.

At that time, the KR were represented abroad, and in particular in Paris, by Khmer intellectuals—French educated and often married to French women. Some had attended grandes écoles like Polytechnique and were the smiling faces of a movement hardly anyone believed to be as vicious as it turned out to be. The [American-backed] Lon Nol regime was so bad, so corrupt, so violent, so racist that it was difficult to believe the other side—which was most creative in its propaganda work—could be as bad, or even worse. Until revelations started pouring about the KR’s bloody regime. As for myself, in the last days of the Lon Nol regime, I had had to take shelter in the French embassy [in Phnom Penh] as LN’s brother had threatened to have me killed after Le Monde had published an article accusing him of being a corrupt criminal.

Of course, disillusionment—this is the very word you quite rightly used—came fast as news filtered from Cambodia to France and the U.S., showing that many analysts had been overly optimistic about the KR, to say the least, myself included. Just as I was to be disillusioned with the regime the Hanoi communists imposed on all of Viet Nam, which eventually had those Vietnamese with whom I had been in touch during the war branding me as a CIA agent ! As you probably remember, the atmosphere in Asia was not always easy in those days….

The quote [by Decornoy] you mention was from July 1975, just after the fall of PP. You can certainly find other articles and studies of these days, including in the US, having said the same things, including probably your former NYT.

Not exactly. Because by then, I would already have become quite disillusioned with the Khmer Rouge, having met their victims even before the true holocaust began within days after they’d move into the Cambodian capital, or PP as it was so fondly known by old Indochina hands. But more about that momentarily.

Meanwhile, I had a couple of final tastes of the good life that Paris could offer before heading for the airport and my flight to Asia. My first night after landing, I treated myself, solo, to a fabulous meal laid out by Michel Tounnissoux, the two-star chef and patron of Chez Michel on the rue de Belzunce in the 10th arrondissement.

On earlier visits, Michel had become my friend, and knowing that I was heading off to war, or at least to a war zone, he pulled out all stops—especially duck two ways and of course a plateau of the finest fromages.

Clyde Farnsworth, the veteran Times correspondent, then based in Paris, spent hours over lunch on Saturday, offering sage counsel from a lifetime of pinballing from crisis to crisis for the paper before settling into a more sedentary role as European economic correspondent. Clyde Henri Farnsworth had spent the bulk of his career overseas—civil war in Cyprus, the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia, student riots and unrest in France.

His DNA was more that of a journalistic aristocracy—his father having crisscrossed China for the Associated Press during World War II and chronicled the aftermath for Scripps-Howard newspapers. I drank it all in, with gusto.

All in all I was pretty pumped up as I piled into a taxi before dawn on Monday morning, February 24, heading for Charles de Gaulle airport at Roissy, then barely a year in operation. My flight was TWA #810, operated by the venerable American carrier, which would finally give up the ghost, disappearing into the American Airlines family in a celebrated bankruptcy 26 years later, but not before its flights had provided me with no end of exciting stories. At the time, though, it was operating non-stop from Paris to Bangkok, part of its round-the-world route that originated in Boston. I managed to drag my two immense pieces of baggage to the check-in. One was my elegant new, T. Anthony green canvas with beige leather trim of which I was ineffably proud, and which I would shoulder to every corner of Asia and across Europe before it finally gave up the ghost. It was filled with every possession I felt I might need before my big shipment arrived in Saigon from New York to set up our new apartment there.

The second bag was my hard-shell Delphi which contained all the tinned food that I expected would keep Schanberg and me well-fed for weeks of war duty that lay ahead. I wrestled this behemoth onto the scale—which in those days consisted of a flat, steel platform tied to an enormous round clock-like dial about three feet in diameter with a large red needle. As I settled the bag on the scale, the needle immediately pivoted clockwise, pinning itself to the furthest end—basically off the scale. The gentle French ground hostess was speechless, her jaw dropping open. “My goodness,” she finally managed to exclaim, “I’ve never seen it do that.” At any event, we finally negotiated a (very much) “overweight” fee, and at 8:30, I was in my seat as the plane taxied down the runway and I was off to Asia.

It was a long way from Paris to Bangkok—18-plus hours to be exact, so at 9:05 the next morning (3:05 am in Paris, 9:05 pm the night before in New York), I stumbled off the plane at Don Muang Airport in Bangkok, a wave of heat and humidity hitting my face as I walked through the door and down the steps to the waiting bus that would ferry me to the open terminal building. It was a good 95 degrees, this being the cool season in Thailand, so it was to my great relief that the ancient taxi finally deposited me at the Hotel Siam Intercontinental downtown.

There was no doubt in my mind that I was back in Asia. The trip in from the airport was like nothing I’d experienced on my last visit to the Orient. This was quite clearly the Third World (as it was called then—the developing world today). The tiny taxi's air conditioning consisted of rolling down every window to allow in the thinnest zephyr of air, mixed with the densest black road-soot from the hordes of cars, taxis and motorized samlors, one step above pedicabs, that belched noxious fumes into my face—all moving at only the most glacial pace, locked in a slow-motion tango of eternal traffic. The Intercon, however, was a golden chilled oasis in the midst of the steaming chaos. While its gardens were lined with stately palms and fragrant local blossoms, the rooms were cooled to a perfect 70 degrees, the humidity, smoke, fumes and pollution all carefully filtered. Bliss.

There were far fewer world-class hotels in Bangkok of the 1970s. The venerable, colonial-era Oriental down by the river, the Erawan next door to the Sporting Club, and the Intercon were a trio of the best. The Intercon, however was the closest to the airport, and in this city of impenetrable traffic, every block could mean a half of hour of your life that you would never have back, so it was often favored by the itinerant press. It was also the closest to the Reuters bureau where visiting hacks often repaired to file their copy. Still, that was not my priority. I was there only in transit—one evening and I’d be off again, headed for Phnom Penh and the war.

So, the next day at noon on February 26, I and all my luggage were on board a venerable twin-engine Air Cambodge prop plane that somehow managed to get into the air. The flight itself was unremarkable. Only the landing still sticks in my mind five decades later.

It was a clear, cloudless sky as we began our descent over the rice paddies and coconut palms of the Cambodian countryside—an apparently tranquil and hardly unusual panorama for an Asian destination. Suddenly, however, the plane began to execute a quite curious maneuver—a series of downward spirals. Round and round we went, in ever tighter, ever lower circles until we finally touched down. It was, I would later learn, the “falling leaf” pattern—designed to thwart enemy gunners from the ground who might, indeed apparently often did, target incoming flights from the west. We touched down at Pochentong Airport and taxied quickly to a large three-sided enclosure of sandbags, piled above the level of the plane. The door opened, and I stepped out gingerly onto the tarmac.

There, waiting at the bottom of the stairs was Sydney Schanberg. Clad in a khaki bush jacket, as was I, heavily bearded and with sunglasses, he gave me a quick appraisal, then said simply in words that I can still hear to this day, “What are you standing there for? They’re shelling the airport, run for it.”

I looked up at the small three-story terminal building and realized that rather than a wall of glass windows, it was simply a wall of aluminum window frames. All the glass had long ago been blown out and clearly those who were in charge had recognized it was futile even to consider replacing this relic of a bygone era. So as Schanberg suggested, I ran for it, hard on his heels. “Don’t worry,” he shouted over his shoulder, as though I had even considered the issue, “the drivers will get the bags.” Welcome to Cambodia. Welcome to my first war.

In fact, I’m not really sure, thinking back, that the Khmer Rouge (or KR as we knew them) were even shelling the airport that day. I suspect this may have been just a bit of the theater that Schanberg loved to indulge in. Still, we headed down the narrow, divided road into town, going a good 70 miles an hour—the wrong way. We were on the left side. I gulped. Schanberg and our driver could see I was a trifle uneasy. “The KR artillery are just within range of the right side of the road,” he explained rather nonchalantly. “But their shells can’t quite make it to the left side. Out of range.” Perfect. That made me feel nice and secure.

The evidence that I’d arrived in the heart of a war zone was all around as our car slowed at the outskirts of Phnom Penh. Without question, there was still a vibrancy in this city. After all, it was sheltering some two million people—a far cry from the 50,000 who called Phnom Penh home back in the lazy French colonial days of 1954—but now swelled to overflowing by the surge of refugees, driven into the center of an iron circle the Khmer Rouge was slowly tightening around the nation’s capital. Indeed, this was one of the saddest realities.

Though I was in the center of one of Asia’s oldest civilizations, I was barred from even a glimpse of its birthplace. Angkor Wat, the vast temple complex that dates to 1200, when it was built as his capital by King Suryavarman II, is 200 miles to the northwest along Highway 6, just outside the regional capital of Siem Reap. This vast interior of Cambodia had been seized by joint North Vietnamese and Khmer Rouge forces as early as 1972. By February 1975, as I was to discover first-hand, I could really see none of the country beyond a five or ten mile radius from the central square—and with some adroitness could actually visit all four fronts in a single day, if there was any reason to do so, which fortunately, there never was.

But the vibrancy of Phnom Penh was merely a façade. This was a city gripped with fear of what was in store, and indeed the increasingly vivid and deadly realities of everyday life. Each day some new salvo of rockets and artillery would send shells, all but randomly, into every quarter of town. The 105-millimeter American-made howitzers the Khmer Rouge had seized during the four years of battle with U.S.-backed forces and now turned back on their foes together with 107- and 122-millimeter rockets, led to some formidable, and quite deadly barrages.

The reporters gathered in their hotel would listen for the direction of the telltale blasts, then pile into cars and go racing off to track down the mayhem they’d unleashed. Two weeks before my arrival, Schanberg had found one of these sallies—a Chinese-made 107-millimeter rocket—struck the classroom of an elementary school in central Phnom Penh at 9:30 in the morning while class was in session. Some thirty children were studying French in the Wat Phnom School. Fourteen, all under the age of twelve, were killed, at least two dozen others wounded by the “shrapnel fragments [that] rained on the children through the thin corrugated room."

—British Pathé

“In the small schoolyard, children were running everywhere—bleeding, shrieking uncontrollably and sobbing in shock,” Schanberg reported. “Weeping teachers tried to help the wounded and calm the others. Blood was over everything, including across the blackboard, where French nouns were chalked. On the floor of the classroom lay bodies in pools of blood.” The force of the blast had apparently propelled some body parts into the nearby trees where they were embedded in the trunks, though such gruesome details did not make it into the paper. I’d read this story before my arrival. Nothing could prepare me for the horrible reality.

But when I pulled up to the Hotel Le Phnom, early on that steamy, sunlit afternoon, all that was immediately apparent of the war were the windows. Quite simply, there weren’t any. Just as the case with the airport terminal building, they’d all long ago been blown out. For the next two months, I’d sleep in my bed surrounded by mosquito netting to keep these pesky, and all too often malaria-carrying, winged horrors from alighting on me and working their nastiness in the heat of the night. I had, of course, come equipped with an ample supply of Atabrine pills, which served as both anti-malarial and anti-giardia purposes. And after my brush with the latter in Leningrad, I was delighted to learn this sideline attribute.

The hotel was by far the best in town, indeed about the only one with any vestige of western amenities. It had once been known as the Hotel Le Royale—but that was when there was a royal family in charge of Kampuchea. Before the war, it was the preferred hostelry for such celebrity visitors as Charlie Chaplin, Andre Malraux, W. Somerset Maugham and Jackie Onassis. When Prince Norodom Sihanouk threw his fortunes in with the Khmer Rouge and decamped to Beijing, the military government of President Lon Nol simply changed it to Le Phnom.

When the tables were eventually reversed, it reverted to Le Royale and eventually would join the ultra-luxury Raffles Group out of Singapore. But that’s way ahead of our story.

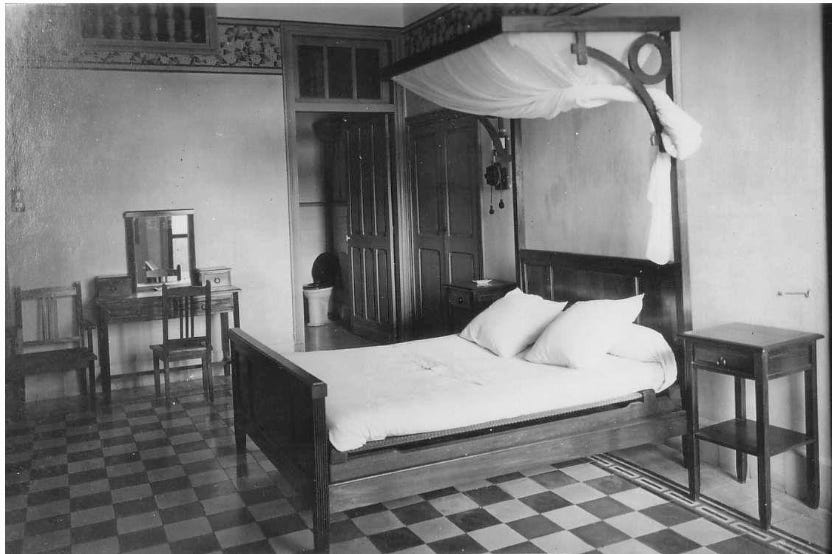

There was no lift, of course, so a collection of bellhops and other desperate individuals humped my luggage up to my second floor digs, just down the corridor from Schanberg’s corner suite. My room was hardly shabby, at least as size went—about half the size of a basketball court with huge French doors that opened out onto a narrow balcony, where I rarely ventured. There was a checkered linoleum tile on the floor—how terribly efficient.

There was no electricity—except for a couple of hours once or twice a week, or all night whenever an army general was in residence with one of his lady friends, an occurrence devoutly prayed for. On those halcyon evenings, there would be the blessed relief of air conditioning, the ancient window units chugging to life at least for a brief moment.

At the same time, we’d rush to fill the bathtub and sink with water since without electricity the pumps would not work. The rest of the time, we ladled water into the toilets, scrubbed up as best we could, all too often taking a French shower (a bit of cologne to mask our unmistakable stench). As for our stories, we banged them out on our flat, blue-green Olivetti Lettera 32 portables by the light of a kerosene lantern or two.

The next morning, I came down to my first breakfast in Phnom Penh. It was pretty thin gruel. Actually, no gruel at all really. My regular breakfast, for as long as I can remember, consists of a large glass of orange juice, preferably with pulp, and a large bowl of cereal with berries and skimmed milk. About the best I was able to manage in the sprawling dining room of the Hotel Phnom, the large ceiling fans turning slowly overhead, barely stirring the steaming air, was a bottle of orange Fanta (usually warm), several dinner rolls, and a cup of mud that passed for coffee.

Well, not so bad, you’d think—a nice continental breakfast—until you tucked into the dinner rolls. There, threaded throughout were small black dots. Not poppy seeds. Rather, the baked remains of the tiny weevils that had infested virtually all the flour available in the country. I mean, after all, they had to live too. Simply some “added protein,” smirked British Sunday Times reporter Jon Swain, a certified Old Asia Hand.

Swain was the first among a collection of truly brilliant, indescribably courageous, dashing hacks, photogs and TV producers, camera and sound folks. They were largely male, but the occasional female who were themselves even more out there than their male colleagues. On my first morning, a bunch clustered around the table, prepared to greet their new, young and incredibly green colleague from the “other” Times. That would be me. Several became lifelong friends. After all, it was difficult not to share these hardships, even for a matter of weeks, and not acquire some profound, ineluctable bonds that transcended decades, even lifetimes.

Next time we pick up the story of the final days of Cambodia with (some of) the characters who populated my world…..

Remarkable times you found yourself in, I'm glad you made out unscathed, perhaps there were reoccurring nightmares. I commented to you previously about our concern about are June visit to the Basque region of Spain and the reception we'll receive from the locals my wife and I being Americans and our awful president Trump who we did not vote for and want him gone. What say you now? Last time you said they will like are money, Im not so sure. James A. Cousineau

Sparkling, not inflammatory, I love the old-school precision of the prose, can hear the ch-ch-ch, chchchch of the typewriter keys of a narrator living history as he writes.