Unleashed Memoir #5: On the doorstep of the world

In which the author finally, as he embarks on the fourth decade of his life, succeeds in attaining his long-sought goal: posting as a foreign correspondent. With ever so many adventures to come.

On October 6, with my beloved wife of the past quarter century—Pamela—I celebrated the 80th anniversary of my presence on this planet among my fellow citizens of the world. As it happens, it also marks the half century (50 years) since I embarked on my life as a foreign correspondent, observer, and chronicler of more than 90 lands far from my own. To commemorate this, another moment from my own past, frozen in time, you will find here an excerpt from my memoir, "Don't Shoot, I'm an American Reporter,” which is still being written. From time to time, Unleashed Memoir will present excerpts from this work where and when they resonate especially. And in this excerpt, I am introduced to the title of this memoir, so many years and adventures in the future. My next step will be abroad.

One evening in late September 1974, my life changed—as only the most incredibly haphazard events in our remarkable business, and at that remarkable institution, The New York Times, could change it. Susan and I had just located our dream apartment. It was a rental, at 1009 Park Avenue, on the second floor, and was one of the few remaining buildings on the avenue that had not yet succumbed to the wave of co-oping that had taken most such apartments out of the rental ranks and into the stratosphere of ownership. This building was owned by the Rose family, one of whose heirs, Gideon Rose, is today the editor of Foreign Affairs, the journal of the Council on Foreign Relations.

As it happens, Susan’s Grandma Bearnot, played bridge with the matriarch of the Rose family and mentioned that her granddaughter and new grandson-in-law were in the market for an (affordable) rental in a nice area. Well, Mrs. Rose's grandson might have just the ticket. And so there we were, starting to measure the living room overlooking Park Avenue for draperies, when I found myself standing at the rear entrance to the Times building on West 44th Street in a driving rainstorm praying for a taxi.

Just to the left of Sardi’s

The rear door was at the foot of a stairway, between Sardi’s and the loading bays where newsprint was loaded into the basement storage areas during the day and the printed papers flew onto trucks during the evening and through the night in those days when the mammoth presses churned out on West 43rd Street every edition of the paper that then made its way around the city and the world. The stairway led upward to a rear door on the third floor that opened directly into the newsroom.

At lunchtime, this exit was frequently used by senior editors or the better-compensated star reporters to duck just next door on 44th Street into Sardi’s, the executive watering hole for Times folk. It was also the preferred egress, particularly in inclement weather thanks to an overhang, for any Timesmen who lived on East Side, since 44th Street was one-way heading east, and the direction taxis would be heading.

So, there I was one evening, just after deadline, at the bottom of the stairs, finding myself standing next to Jimmy Greenfield—still the paper’s foreign editor and successor to the chap who’d hired me, Seymour Topping. Greenfield who quickly sized up the fact that I was heading in his direction and seeking a cab, proposed that rather than fight each for the first one to come along, we’d share. And sure enough just then, up pulled an empty yellow hack. We poured ourselves, still relatively dry, into the back seat, Greenfield gave directions, and off we sped.

At that point, to keep the conversation alive, Greenfield inquired how I was doing, though he clearly had little interest in goings-on at the metro desk. “Fine,” I answered brightly, “though I’d sure rather be overseas.”

There was a short pause, and as I looked over, saw an expression of surprise passing across his face. “You would?” he asked, genuinely astonished. “I had no idea.”

“Oh, yes, sir, in fact that’s the reason I came to The Times.”

And that was it. We moved onto other subjects, and I imagined he’d quite forgotten all about it when he deposited me on Madison Avenue at East 67th Street, where we were still living in Susan’s apartment. He continued on his way in the cab.

But as with most things Greenfield, this was hardly forgotten. You didn’t tell things to Jimmy Greenfield without consequences. There were consequences, indeed. Because three weeks later, Abe Rosenthal, the redoubtable executive editor of The Times, summoned me into his office. This was not a trivial event in the life of any Times reporter and by the time it did happen, on my end at least, I’d quite frankly all but forgotten my conversation with Greenfield in the press of the daily life of a general assignment reporter.

Abe & Jimmy

So, as I began the long walk from my desk in the center of the newsroom to the rather intimidating precincts of the office of the Executive Editor, all sorts of horrible scenarios coursed through my head—beginning with the latest stories I’d been covering—particularly Nelson Rockefeller, everything from his FBI check en route to the vice presidency to his list of $24 million in charitable contributions, which led the paper on October 20 as his endless confirmation hearings dragged through the Senate….

….to his wife Happy’s cancer surgery, to the city seeking more compensation from Blue Cross for mental patients, which wound up above-the-fold on my thirtieth birthday, October 6, 1974.

I’d even made page one when Burton N. Pugach married Linda Ross, his girlfriend who he’d tried to blind 13 years earlier by hiring three thugs for $2,000 to throw a bottle of lye in her face so that “no one else will want you.” Hard to believe his nuptials would wind up even on the bottom of the front page of America’s newspaper of record on a day when the GOP lost the United States Senate by virtue of a Democratic win in a New Hampshire by-election; and Christian Barnard, eagerly tried a second-heart transplant operation in Capetown, South Africa. But this was the new New York Times, which was considering every remaining newspaper in New York City as a rival. And the tabs were having a field day, yet again, with Burt Pugach, who’d just been discharged after fourteen years and one month in prison for the attack in a case that went all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court—“an early test of the legality of wiretaps as evidence,” as I wrote.

Which, come to think of it, may actually have rationalized this seamy story winding up on the front page. As it happened, Pugach himself actually phoned me right after their wedding to announce, rambling on and on, in a heart-tugging but utterly bizarre conversation, “Maybe she loved me all along.” By this time, neither having married, he was forty-seven and she was thirty-eight. As I’m writing this, incidentally, in 2013, Linda just passed away, still loving her Burt, still married to the very end. Just another Forest Gump moment.

As I walked into Abe’s office, my prayer was that he wasn’t going to assign me to some permanent purgatory like the city hospital’s beat, which I’d been doing a lot of lately, and thoroughly detesting, though the execrable state of the hospitals and their finances under the city’s new mayor, Abe Beame, was quite a certain route into the paper and even onto the front page with some regularity.

But Abe had very different matters in mind. And, not surprisingly, got right down to the point.

“How would you like to go to Saigon?” he smiled.

Of course, with Rosenthal, that was not a question. Not if you expected to have any career at the paper. He ran The Times like the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff ran the Pentagon. You don’t ask someone if they wanted to do something and have them say either, “let me think about it” or “I’m not sure.” You simply said, “how high?”

And the answer was inevitably: pretty damned high indeed. So, instead, I said simply, “When do I leave?”

Well, not for a while, as it turned out. It was all pretty complicated. The Times’ Saigon bureau was quite a vast undertaking. Smaller, certainly, than at the height of American military involvement before the Paris Peace Treaty brought at least a temporary cease-fire and withdrawal of U.S. forces; smaller, too, than bureaus maintained by the major wire services or the American television networks, it was still the largest newspaper bureau in Vietnam. I’d be replacing Jim Markham, who was heading off to Paris for The Times where he would serve as bureau chief until his death 15 years later at age 46 from a self-inflicted gunshot wound.

At the same time, it was also to a degree a backwater by that time. The year before (January 27, 1973, to be precise), Henry Kissinger and North Vietnam's lead negotiator Le Duc Tho together with the Provisional Revolutionary Government (Viet Cong) foreign minister Nguyen Thi Binh and a very reluctant South Vietnam president General Nguyen Van Thieu, had signed the Paris Peace Accords ending the decades long wars in Vietnam. (Kissinger and Tho would share the Nobel Peace Prize.) The final ceasefire went into effect the next day. American troops had largely pulled out pretty quickly, taking with them a lot of the interest of our readers—thoroughly sick of this horrific slaughter that had taken a swath of a generation of Americans with it.

Still, the conflict had equally produced a generation of journalistic superstars, many of whom cut their teeth on the conflict and went on to the highest levels of their profession at The Times and a host of other papers, magazines, and broadcast networks. Seymour Topping served in Vietnam as a young Associated Press reporter even before he ever joined The Times and Malcolm Brown, who I would succeed as East European bureau chief in Belgrade, had won his Pulitzer there for the AP.

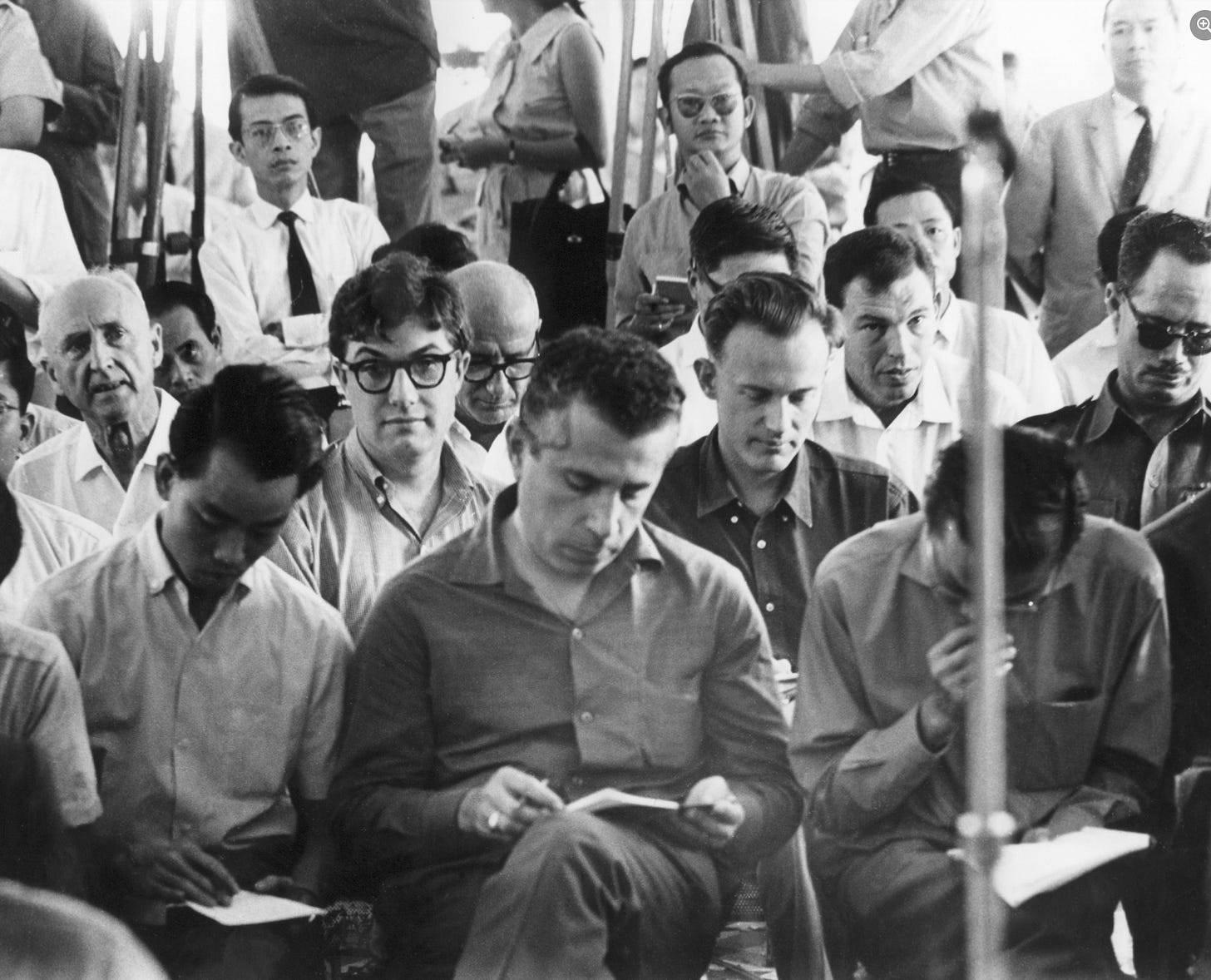

The '5 o'clock follies,' the daily US military briefing at Saigon's Rex Hotel as the war was grinding on…Malcolm Brown behind Seymour Topping at the debut of their careers.

By the time I was tapped, however, that was all largely history and it had begun to look like Vietnam would follow the Korean peninsula into a centuries-long, metastable division between North and South with the occasional skirmishes between forces on both sides, observed or counseled in Saigon by a relatively small cadre of Americans. Few of us, however, had ever really understood the North's determination to succeed in uniting the two halves of their nation and how quickly that might come about now that the US had largely washed its hands of the whole affair and walked away.

Getting onto page one at that point was hardly a slam dunk. And there were probably few in The Times newsroom truly eager to step into such a backwater where there were fewer front page bylines in the months before my departure than I'd managed to accumulate on Metro. So, Abe had turned to me.

Still, now my time and opportunity had come to join the foreign staff, and I leaped at the opportunity. I had waited (or been made to wait), as it happened, until the exact age of 30. Except under the most unusual circumstances, Abe had never wanted a Times correspondent to serve overseas before his 30th birthday. The ostensible reason was that "you still hadn't made all your mistake yet, and while you could make mistakes in New York, overseas you could touch off a war.” But the real reason, many suspected, was that Sulzberger family scion C.L. Sulzberger had somehow found fault with Abe and kept him from taking on his first foreign assignment (New Delhi) til he had turned 32.

Still, before my departure, Abe did want me to learn some Vietnamese, and then there was the matter of a newly-wed. Not that such a trivial matter should concern a newly-minted foreign correspondent.

I walked out of the office my head reeling and my feet a good six inches off the linoleum. That night I told Susan where I was headed. And level-headed gal that she was, she promptly responded, “Well, we’d better see how we can get out of that lease at 1009.” Right, Park Avenue. The lease. And we’d just measured for the curtains. Thank heavens the velvet hadn’t been cut, or any cash changed hands.

So, the wheels began to turn. The first issue was Vietnamese lessons. Since the time for my departure was not so far in the future, these had to be total immersion—eight hours a day, six days a week. Only Berlitz was able to muster that kind of muscle on short notice. Berlitz it was. The metro staff was now in my past. My future was in the hands of a funny little Vietnamese importer-exporter, who moonlighted or, in my case, daylighted, as one of Berlitz’s top Vietnamese language specialists. I must confess that, having never truly had the opportunity to use this tongue first-hand—as readers who stay with me will shortly discover—only one phrase still sticks in my mind. It was from our first day of lessons.

“Soooo, you are going to Sai-gon as correspondent,” my instructor smiled. Yes indeed. “OK, I will teach you one phrase that may save your life. Repeat after me. Đừng bắn, tôi là một phóng viên Mỹ.”

I dutifully repeated, “Đừng bắn, tôi là một phóng viên Mỹ,” or something that vaguely approximated that, then paused. “So, what does that mean exactly?”

“Don’t shoot, I’m an American reporter,” my tutor shot back.

We both cracked up, clearly aware that of course that phrase was never likely to save the life of a chipmunk, let alone a Times reporter with a Viet Cong rifle pointing at him.

“OK,” I finally managed to gasp, “if I ever write my memoirs, that’s the title.” And so it is, now a half century later.

Still, I also got him to teach me how to substitute ‘Canadian’ for ‘American’, should push ever come to shove. Shortly into our lessons, he confessed, somewhat apologetically, that he was actually from North Vietnam. I told him I didn’t care if he reported back to Ho Chi Minh, all I wanted to do was learn Vietnamese.

Ah, but there are several different Vietnamese dialects, he replied. The Northern dialect was effectively the purer. It had six different tone levels—so many words, pronounced with six different inflections, could means six entirely different things. Southern Vietnamese had only five tones, and that was what he would attempt to teach me. Attempt is a very appropriate word. Since, barely able to carry a tune myself, capturing these tonal nuances caused me no end of grief. About all that got me through was my perfect pitch—my ability to hear, if not repeat back, each of the nuances in question. Motivated by my first foreign assignment, then, I pressed forward….

I also did, of course, have to wind up my time on the metro desk, where editors suddenly began looking at me just a trifle differently, given my imminent transformation from the chrysalis of a general assignment drudge to the butterfly of a foreign correspondent, even if I’d already long been equipped with my Burberry trenchcoat and Rolex GMT Master wristwatch (which Topping, who'd hired me on the foreign desk six years earlier, had told me were the marks of a foreign correspondent returning from his first foreign assignment). So, to my increasing astonishment, I managed twenty appearances on the front page between my return from our honeymoon and the end of 1974.

There was the three-column headline on my p.1 story “Policeman Found Dismembered Here; Was to Testify at a Department Trial,” chronicling how the hapless officer’s nude body, chopped with a knife and a meat cleaver into seven pieces, was stuffed into a blue plastic bag outside a Chinese laundry on West 79th Street.

He’d been scheduled to testify at a departmental trial, but that turned out to have little to do with his demise. Three days later, my colleague Michael Kaufman, who would later distinguish himself as he followed me to Eastern Europe for The Times, made the front page with the arrest of the perp—a 31-year-old ex con, Julio Vazquez, who’d done time in Attica penitentiary where he worked in the butcher’s shop, as well as two young women in whose apartment the murder and apparently the assignation that led up to the officer’s murder had taken place. Seems the hapless officer Kelly had a drinking problem and rather enjoyed the company of comely prostitutes. (The Times did run their photos.). Ah life, and especially death, in the big city….

But it was not until January 10, 1975, that my language lessons and studies of Indochina would come to a close, together with my life on the Metropolitan Desk as I headed abroad to my first foreign assignment.

Stay tuned for some quite extraordinary denouements.

Happy 80th! Such a life, so far. Such a happy remembrance of NY Times' past. (The NYT today says that you could enjoy life to 150.) Onward....

To 150 … if I were born today … sadly my birthdate was 1944 !!!

;-((

But thanks for the kind good wishes !!!