Unleashed Memoir #4: Birth & death of ‘All the News’

With the demise of WCBS as an all-news outlet, New York is left with WINS….where I began my journey as a journalist in 1965. Coming full circle.

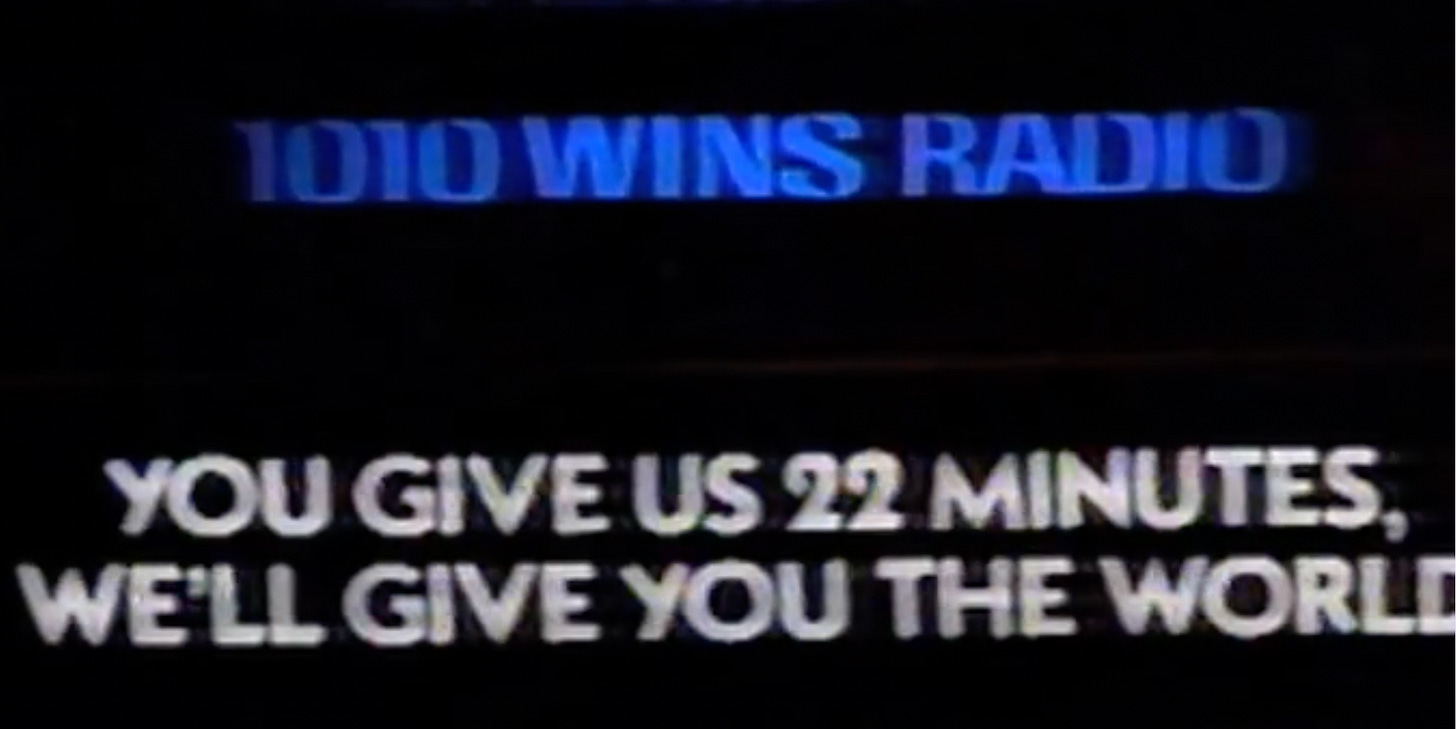

“You give us 22 minutes, we’ll give you the world.” But until the arrival of that epiphanal moment in 1965, there was no streaming. There was no news, but for scattered headlines and a half hour on televison at 6 pm. Newspapers would still rush ‘Extras’ onto the streets for big news and newsboys would hawk them, shouting, “Extra, Extra, read all about it.” Then, suddenly, along came a ground-breaking innovation. It was the summer of 1965 and the owners of top-rock station WINS decided on on experiment—24 hours of news around the clock. No music, just all news, all the time. In bites 22 minutes long. Two years later, a big success, it was joined by WCBS—a second all-news station—flagship of the CBS Radio Network. Now, this week it was announced, WCBS is biting the dust. WINS—the world’s first—will again stand alone in New York. But that summer of ’65, I was there for its debut. It was a magical moment. Worth recalling again, today.

To commemorate this, another moment from my own past, frozen in time, you will find here an excerpt from my memoir, "Don't Shoot, I'm an American Reporter,” which is still being written. From time to time, Unleashed Memoir will present excerpts from this work where and when they resonate especially. I pick up the story at New York’s Columbus Circle….

…on the sidewalks of New York

In the summer of 1965, and just 20 years old, I headed to New York to begin my career as a journalist—breaking the last real ties that bound me to my native Boston. I’d found an apartment on West 104th Street, between Broadway and West End Avenue—a neighborhood of quiet brownstones and pre-World War II vintage apartment buildings, many with doormen. It was just 12 blocks from the campus of Columbia University where I would enroll that Fall in its Graduate School of Journalism. I’d won a Westinghouse Broadcasting summer internship—quite a coveted honor as it turned out. Westinghouse owned a number of major radio and television stations across the United States including WBZ radio and television—then the NBC stations in Boston. I’d developed close ties with NBC during the post-Kennedy assassination days when I served as news director of the nearby Harvard student radio station WHRB. One of the stations Westinghouse owned was New York powerhouse WINS. One of the top rock & roll stations in the country, it had been in a bitter head-to-head competition with WABC and the king of all Top-40, WMCA. Until suddenly Westinghouse took a brave, indeed revolutionary gamble. In the Summer of 1965, WINS became “All News, All the Time.”

WINS had an illustrious history. It began life in 1924 as WGBS, named for its founding owner, Gimbel’s Department Store, back in the days when Macy’s and Gimbel’s dominated New York retailing on opposite sides of 34th Street and Seventh Avenue. By 1932, William Randolph Hearst had acquired the station as part of his expansion into New York by buying the New York Daily Mirror, then in head-to-head competition with the other New York tabloid, the Daily News, where I would eventually find myself thirty-five years later.

Westinghouse took over the station in 1962. But by the Spring of 1965, WINS’s top-40 ratings were being eclipsed across the board. It was tough to compete with the WMCA’s Good Guys—Scott Muni; the Texan, Dandy Dan Daniels; and the housewives’ darling, Harry Harrison. Then there was Bruce “Cousin Brucie” Morrow on WABC. So WINS (“10-10 Wins New York”) was losing—especially hard hit when its high-voltage top jock Alan Freed was indicted for tax evasion and forced off the air.

Even its star, Murray “the K” Kaufman couldn’t help, despite his live “Swingin’ Soiree” and his relentless promotion of himself as “the fifth Beatle.” After he’d used their mutual friends the Ronettes to get him into the Plaza Hotel where the Beatles were staying on their first New York visit, from their suite he broadcast live the new sensations’ first American appearance. So on New York’s rock ‘n roll radio scene, there was a constant game of musical chairs, but when the music stopped WINS was all but left out. By that time, despite all his self-hype, a pathetic Murray was running a distant third to top rockers WABC and WMCA, according to Billboard magazine. In December 1964, Murray had discovered a format change was imminent, and he broke the news on the air. At 8 PM, on April 18, the Shangri-Las “Out in the Streets”—the last song ever played by WINS—ushered out one era in broadcasting and ushered in another. Two months later I arrived at the new, now all-news 1010 WINS.

When I arrived in New York that June to take up my internship, the media landscape was far different from today. There were six daily newspapers; seven if you counted the Wall Street Journal, which did little to cover any part of New York City outside of Wall Street; ten newspapers in and around the city if you added Newsday and the Long Island Press which, at the time, serviced small areas of Queens, and the Brooklyn Eagle. Hearst’s Daily Mirror, one of the three tabloids, had disappeared after the near-catastrophic newspaper strike of 1962-63, which also spawned The New York Review of Books. There were three afternoon dailies—The Post, the Journal American and the World-Telegram and Sun—themselves created by earlier mergers in a town that at its peak had seen nearly a score of newspapers.

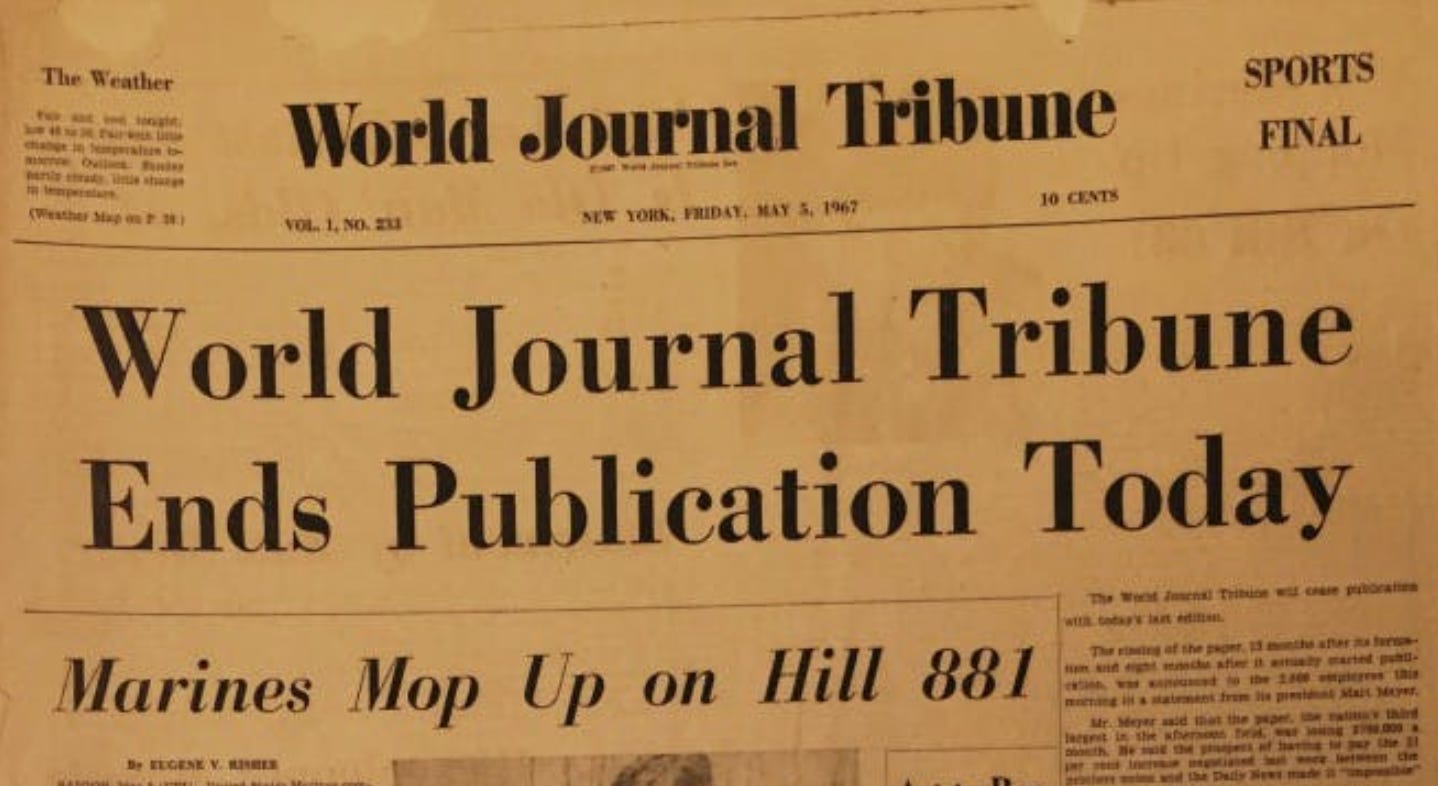

By late Fall 1965, following the second newspaper lockout and strike in five years, the Journal American, World-Telegram and Sun and the Herald Tribune, the latter being both a quality morning rival of The Times and partner (in the International Herald Tribune across the Atlantic in Paris) had linked arms to form the World Journal Tribune, which itself was destined to last just another eight months.

This number of daily newspapers serving what was in 1965 the unchallenged media capital of the world matched the number of television stations—seven, of which just three were true network affiliates. ABC. CBS and NBC dominated the landscape. They were the only national television broadcasters with worldwide news organizations. New York also had four indies—WNEW, WOR, and WPIX (respectively channels 5, 9 and 11), and the public broadcasting station, WNET (channel 13), though the national Public Broadcasting System (PBS) was still five years in the future. The daily ration of broadcast news, however, was quite meager—a half hour on two of the three networks every evening. And that dose had been enlarged from fifteen minutes barely two years earlier on NBC (the pioneer), followed quickly by CBS. ABC didn’t go to a full half hour until 1967. On radio, the news allotment was as meager—five minutes at the top of the hour, fifteen minutes hourly on WOR, elsewhere once or twice day, when behemoths like the daily CBS World News Roundup took the air at eight o’clock in the morning, and there was the occasional bulletin. That’s the way it was, and seemed destined to remain.

Until WINS and all-news-all-the-time came along. It was, most pundits at the time sniffed, a wacko idea. Whoever would possibly want to listen to news all the time, 24 hours a day? A handful of fanatics, perhaps, but you couldn’t build a business or an advertising plan around them. Still it happened. The scene of this revolution was a tiny, three-story triangular shaped building plopped incongruously on a thin triangle of real estate where Broadway and Central Park West converged on the northern side of Columbus Circle—across from the New York Coliseum, a mammoth convention hall that hosted each year the New York Auto Show and a scores of other similarly ambitious events.

When I arrived, the Coliseum was barely nine years old and would linger until 2000 when it was finally demolished to make way for Time Warner Center, a mixed-use colossus that was, indirectly a product of the revolution in media conglomerations that even the most prescient would have been unlikely to foresee in 1965.

Eventually, the oddly-shaped little building whose three flights I climbed each day to the tiny newsroom of WINS would give way to a 45-story tower, known first as the Gulf & Western Building, and which in turn morphed into today’s Trump International Hotel and Tower. In the Fall of 1965, WINS moved to brand new digs in a sparkling high rise at 90 Park Avenue just south of Grand Central Station.

But that Summer, ground zero of the media revolution was the small, triangular-shaped newsroom of WINS attached to two tiny broadcast studios. As a Group W intern, I was little more than a glorified copyboy. There were two of us during most of the daytime shifts—myself and Dick Stokvis, a native Philadelphian who’d pitched up via Syracuse. His first love was sports, not news, and as our internship ended at the end of the summer, and I returned to school at Columbia, he moved quickly into his first love as a sportscaster. Changing his name to the more broadcast-friendly Dick Stockton, he returned to KYW-TV, also owned by Westinghouse, in his native Philadelphia before moving quickly onward to fame and fortune as the voice of the Boston Celtics, the Red Sox and then onto network sports.

But in the Summer of 1965 we were at the beck and call of the small army of young men who manned the typewriters and microphones of WINS. (I can’t recall a single woman on the news desk or on the air at its debut—years before equal opportunity became a reality in the newsroom and the nation.) The pressure on each of them was inexorable, the demands of this 24-hour marathon of news and information insatiable in terms of raw copy, sound and the means of fulfilling what quickly developed into a bottomless appetite for all they could churn out.

And it had to be both fast and accurate since even professionals in the news business quickly came to rely on it. One, Barry Newman, who’d become a renowned foreign correspondent and page one writer at the Wall Street Journal, recalls that as a Times news assistant at the start of his career, when he was writing ‘news summaries’ with two future Pulitzer prize winners:

Still living at home in Rockaway (Queens), I drove my ’61 Chrysler 45 minutes to (the Times building) on West 43rd street two or three days a week. I listened to WINS all the way. By the time I got in, I already knew what stories to extract from the copy pile on my desk that were sure to make page one, long before the layout arrived. It made me look fast and smart.

Our principal function was to oversee the rows of teletype machines that, 24 hours a day, spewed out news—the raw product of information around the world, all arriving in a small, windowed triangle at the south end of the newsroom. The teletype tickers, whose unceasing click-click-click rhythm was played 24 hours a day as a basso continuo behind every WINS announcer as he read the news over the air, were the real reason the station could provide the kind of programming it did and on the cheap.

“All News, All the Time,” “The Newswatch Never Stops,” “Listen 2, 3, 4 times a day,” and “You give us 22 minutes, we'll give you the world” became watchwords in New York broadcasting, attracting an all but instant audience that made many of its newscasters as instantly recognizable names as Murray the K or Cousin Brucie. They also became friends. There was a trio of Stans. Stan Z. Burns began at WINS in 1944 at the age of 19 and continued as a rock-and-roll DJ, including an extended stint in the long overnight hours, until the all-news switch snatched from under him his prime 6 to 10:30 pm time slot and propelled him onto the news desk, still behind a WINS microphone. Stan Bernard, another top-40 holdover with a ninety-minute “Contact” show on WINS, had been sandwiched between Murray the K and Stan Z when this Stan held down the overnight rock and roll slot.

But Stan Brooks was our leader—a dyed-in-the-bone hard-news newsman, a reporter’s reporter. Beginning his career with eleven years at Newsday before joining WINS in 1962, he had risen to news director when its format was rock ’n roll. In December 1964, the brass came to him with the top-secret news that they were going all-news, all-the-time. Stan promptly assembled a remarkable staff. In four months, under his leadership, they were ready to go. In January 2012, I ran into Stan in the Manhattan Ford dealership where we were both bringing our cars for servicing. At 85-years-old, he was still on the air, still the leathery street-smart reporter, a half-century since he first went before a WINS microphone.

There were other players, too who distinguished these early days. Doug Edelson was the oldest, at forty-one, eventually parking himself for decades in City Hall’s venerable Room 9, a warren of cubicles and desks that populated a teeming pressroom where even Hildy Johnson might have felt right at home.

All were large-than-life icons who I admired intensely, yet apparently as far out of reach to me, a summer intern, as any president or rock star. Each brought his own sense and sensibility to this exciting experiment. We were, effectively, a non-stop talking tabloid in a city that still possessed two print versions that were hardly reluctant, in the face of a big story, to rush out “Extras” at a moment’s notice, and hawked at train stations and street corners by newsboys. I suspect we played a central role, of course, to bringing an end to such quaint monuments of an industry that history was all too rapidly passing by.

Each day, I watched with fascination as the carefully oiled machine that was WINS evolved, grew and morphed with the very environment we were covering. This was a seminal moment in New York. Coming to end was the twelve-year reign of Robert Wagner as Mayor—the longest since the rule of Fiorello LaGuardia from 1934-1945 and that would be matched only twice again—by Ed Koch and Michael Bloomberg. Each was a giant in his own fashion. Wagner’s son Robert preceded my son at Manhattan’s Buckley School then Phillips Exeter Academy, and as a member of Harvard’s class of 1965 had marched through Tercentenary Theater with me. His father had placed his own mark on the city and WINS was very much in a position to chronicle this—and his eventual handoff that Fall to another Ivy League soul mate, John V. Lindsay.

Though for a time a creature of Tammany Hall, by the time we went on the air Wagner had broken from the boss structure that had for so long held the city in its grip. In the process, he built public schools, launched the City University of New York, allowed municipal workers to organize into unions, banned housing discrimination based on race, creed or color, and became the first mayor to bring large numbers of people of color into city government. On his watch, ground was broken for the 16-acre complex that would be known as Lincoln Center, and Shakespeare came to Central Park. In the fall of 1957, after the Dodgers and Giants decamped from New York City to California, he named a commission to bring National League Baseball back to the city, and in the Fall of 1962, the Mets played their first game in the Giants’ old home in the Polo Grounds, nestled between the Harlem River and Coogan’s Bluff at 155th Street and 8th Avenue. In the summer of 1965, when I pitched up in New York City, the Mets began playing their first full season in Shea Stadium in Queens.

WINS covered all this and much more. Of course I was very much an observer—my nose still pressed against the glass, but at least in the front row now observing the excitement, while acting as little more than water boy to the starting squad. Still, I was watching and learning. I watched as the news editor and news writer (one on each shift) plus the anchor for each 22-minute segment, carefully crafted the product, writing headlines, copy, selecting the “actuality” or tape that would enliven the action, choose where to cut to a “live feed” from a reporter in the field, often via a payphone on a street corner, or a taped report from afar. I’d watch the tape editors carefully manipulate the large reels, carefully place the quarter-inch, thin brown vinyl on an “editing block”, slice apart two segments, then carefully stitch them together with tape, their ears glued to the product to make certain that it a seamless sound was produced. And they would perform these acts of extraordinary legerdemain on the tightest deadlines, editors and anchors breathing down their necks. By mid-July, I was as much at home in this pressure-cooker atmosphere as I was in student radio WHRB’s basement digs in Memorial Hall at Harvard.

My first summer in New York was itself quite memorable. I was living with two roommates—one who’d just graduated Harvard with me, but who I barely knew before we linked up, and another who was a couple of years older. The neighborhood was a typical old Upper West Side nabe. West of Broadway, the old brownstones and high-rise pre-war apartment houses began, many with doormen, stretching down to the lavish palaces on West End Avenue and Riverside Drive with their fabulous Hudson River view across to New Jersey. Our flat was a simple, old ground floor flat in a most decidedly non-doorman building. We had a key to the front door and an intercom-buzzer would let in friends. I generally ate on my way home from work—often around the corner at a small greasy-spoon where, for a buck or two, I could get quite a passable cheeseburger, fries and a salad. I had little to do with my two roommates, apart from one incident that stands out especially.

It was a Saturday evening (I worked nearly every day that summer), and I’d just come home from a long day refilling the news tickers and distributing their output to the editors and anchors. I threw my coat on the bed and walked into the kitchen for a nightcap of a glass of chocolate milk. The kitchen was a large, old linoleum-floored rectangle with a wooden table in one corner and a big enameled gas range in another. I switched on the light and there, in the middle of the floor was the largest insect to which I’d ever come face-to-face in my life, spent in a spotless Boston suburb and a Harvard dorm. Honestly, it seemed large enough to have thrown a saddle across and ridden out of the room. I screamed. Loudly. Our older roommate came racing into the room waving a handgun. “Where is he, where is he?” he shouted. I pointed dramatically, to the floor, the blood draining from my face. I was all but unhinged, contemplating with split-second uncertainty, which was the worst menace—the creature, still glued to the floor, or my roommate’s weapon.

He lowered the gun. “It’s just a bloody waterbug,” he snarled in his faux-British accent, and exited the kitchen, returning a moment later with a still unopened copy of Sunday’s New York Times. The Sunday Times, in those pre-Internet, pre-cable days, was a not inconsiderable behemoth of at least a dozen sections, and each 40 to 50 pages thick. He tossed it onto the creature, then jumped on it for good measure as I heard the crackle of its shell collapsing under the weight. “There. He’s dead.” He certainly was. My knees were still knocking. But the creature had certainly gone on to meet his maker. Monday morning, the building super and handyman pulled the heavy cast iron stove away from the wall and uncovered, beneath, an entire nest of these disgusting creatures. I slept only marginally better for the rest of the summer. Indeed, for the rest of my life, in the most remote corners of the world, when I happened upon similarly endowed members of the insect species, I was instantly transported back to that horror of my first sighting in the dead of night in search of a simple, restorative glass of chocolate milk.

…crisp, condensed copy that even the most distracted listener could absorb while packing lunchboxes for four children or piloting the Chevy through a five-mile traffic jam…

Not long after I arrived in the newsroom of WINS and sussed out the system, it occurred to me that my real place was not in the wire alcove changing teletype paper and ribbons and stripping the news off the machines, but rather on the receiving end—on the news desk as a writer, banging out copy for the anchors to read. How to get there, though. Not an easy task, as it happens. To do so, I would have to demonstrate my ability to write—especially to write the kind of clean, crisp, condensed copy that even the most distracted listener could absorb while packing lunchboxes for four children or piloting the Chevy through a five-mile traffic jam on the West Side Highway. It had to be at once accurate and, where appropriate, moving. Even to sit down at a newsroom typewriter to demonstrate this ability, which I was quite confident I possessed, meant in turn possessing a union card. This was my highest hurdle. I had none. And to acquire one, I needed a Writers Guild job. It was a vicious circle that seemed utterly closed and that for the rest of my days left me with an ineradicably bitter taste when it came to unions and all they represent—which in my case comprised a barrier to entering the hallowed precincts of journalism.

Eventually, however, I triumphed. Late one Saturday night, as I lingered long past my shift in an all but deserted newsroom, the young duty editor—himself barely a year or two older than I—took pity on me, and at the risk of his job (or at least his union card, which amounted to the same thing), pointed to a typewriter on a table off in a corner, gave me a sheaf of wire copy and said “write me 22 minutes of copy.” My heart gave a leap of joy as I bolted for the typewriter. Barely a half hour later, I was back, the job finished. The editor looked up, astonished. “You’re finished? Let me see.” He skimmed my lines. “Why this is perfect,” he beamed. “I’m slipping this to Stan on Monday.” I could barely contain myself as I raced up the stairs to the newsroom Monday morning. Stan Brooks, the news director, beckoned me into his glass-walled cubicle. “This is a wonderful broadcast you’ve written,” he proclaimed. Then, looking up at me over the glasses perched on the bridge of his nose, his eyes twinkled as he smiled. “Of course I don’t know how you could possibly have done this without a union card.” My heart sank. “But hey, I’m not the shop steward. Still, you’d better join the Guild since you’re going to be working as a news writer.” The gates of Paradise had swung open and St. Peter was beckoning me in. I’m not quite certain how I managed to finish out my shift as an intern, but by the end of the week, I was a news writer for WINS.

Several weeks into my new gig, Stan stopped by my desk and announced that the Beatles were arriving in New York the next day. As the station that, through Murray the K, had taken a lead role in their first visit to the Big Apple eighteen months earlier, it had no intention of ceding this story of the Beatles’ return visit to anyone. It was all hands on deck. This time, for whatever reason (certainly not money), they were decamping from the Plaza Hotel on Fifth Avenue to the Warwick on Sixth Avenue. Inside they were holding their first news conference.

My post was outside. And it was quite a scene. The Warwick was a vintage New York City landmark built by William Randolph Hearst in 1926 for $5 million, situated on the northeast corner of 55th Street and Sixth Avenue. But the fans had taken over the entire intersection, and then some. Indeed, it was my first and biggest experience, until I saw the new Polish Pope return to Poland a decade later, of a crowd gone wild with pure star frenzy. Star f***ng was not a term of usage in those far-off, far more prudish days, but that’s what it was. Most of them were young women, driven wild by their passion for these four young, apparently quite hot men.

And the ultimate irony? They never even got to see one of them. Somehow, the hotel and security managed to spirit them out, past the crowds, past the adulation, to their rendezvous with destiny— Shea Stadium and emcee Ed Sullivan where they would perform for a frenzied crowd who would pay for the privilege.

Indeed, there was never a dull moment. Since I was paying the lowest rent, I’d been assigned the dining room of our two-bedroom flat as my bedroom and study. Of course, that meant not an inconsiderable amount of often-inebriated traffic through to the kitchen at all hours of the night. But one evening, I was alone….when the lights suddenly went out.

I rushed to the front windows and looked up and down the street. Blackness. As it happened, I had a battery-powered radio, so I turned on, of course, WINS. And sure enough it was a blackout. My only thought? Get to the newsroom. I was on 84th Street, just off Central Park West. I bolted downstairs and headed south. No traffic lights. No subways, of course. Total chaos on the streets. It took me 45 minutes to make it on foot the 44 blocks down and five long blocks over to 40th Street and Park Avenue, where WINS had just recently installed itself after its move from Columbus Circle (which would have been just a 10-minute dash from my apartment).

It took me another, breathless 10 minutes or so to make it to Park Avenue. WINS reporters were already careening past me, headed into the street to soak up atmosphere. Then, pounding up 19 floors I found the studios where a resourceful techie had hooked up a phone line to a backup transmitter running off generator power in New Jersey. We’d quickly determined that the entire Northeastern United States had suddenly gone dark. Indeed, for much of the night, WINS was the only station that managed, somehow, to remain on the air. Stan Brooks stage-managed the entire event—and the aftermath—from his tiny office overlooking the newsroom, dark except for the candles and battery lanterns the reporters and we writers were using to bang out copy. Computers, fortunately, were decades in the future—ditto for electric typewriters, which were just beginning to come into their own in high-end offices. But in newsrooms manual typewriters, copy paper and stubby No.2 pencils were still the gold standard.

The great Northeast Blackout was a turning point in so many ways, I recognized, between frantic dashes between the news desk and the studio. The scenario only gradually unfolded, though the human stories were everywhere. For the most part, these involved strangers rushing pregnant women to hospitals to give birth, helping the elderly across intersections with dark traffic lights, a community of New Yorkers coming together. And the plainly amusing—the young boy in Connecticut, heading home late from school with a stick, hitting each telephone pole along the way when suddenly all lights went out, sending him into panic that he’d caused the entire Northeast blackout. But what that evening really did was to cement WINS as a central element in the web of New York. “That night put us on the map,” Stan Brooks would recall later.

For myself, however, it was the end of a chapter. I could see that WINS and Columbia Journalism School were simply too much—doing neither justice, and since dad was shelling out heaps of money for Journalism School, and I didn’t see myself as a WINS news writer for eternity, I bade farewell to the 19th floor at 90 Park. Instead, I plunged into life as a student. Life as a foreign correspondent awaited around the corner.

The skills I learned in those months at WINS would carry me through much of my future career—into newspapers like The New York Times in the city and across the world, and eventually back into radio and television for CBS News.

As it happens, two decades later, I would begin to appear regularly on WCBS Newsradio and on hundreds of other CBS Radio stations across America as an anchor for the CBS Radio Network and as a Paris-based correspondent for CBS News.

So, today’s demise of news on WCBS hits particularly close to home. And a sense of just how far our media has taken us and myself in particular.

I can't tell you how much this means to me, Janet !

& do spread the word !!

;-))))

A great read, thank you.