Unleashed Cuisine: Fine Dining Medieval Style / Part II

More of what royals and ruffians consumed in the Middle Ages, with recipes to excite contemporary palates and challenge today's cooks around the world

This is Part II of the launch of a new feature for Andelman Unleashed exploring the world of food at every level around the globe. On occasion, we will delve far back into history, certainly explore other cultures and civilizations, but always with an eye toward today. Each episode will feature, as well, recipes for dishes that can be prepared using ingredients and utensils available today. And as always, we invite you to experiment and comment.

In this case, we wind up our extraordinary two-part tour d'horizon of medieval dining across Europe….

Our guest expert today, as last week, is Yale's Paul Freedman, the Chester D. Tripp Professor of History. Freedman, among the world's premier culinary scholars, specializes in medieval social history, the history of Catalonia, comparative studies of the peasantry, trade in luxury products, and especially the history of cuisine. His latest book is American Cuisine and How It Got This Way (Liveright/Norton, 2020).

Take it away again, Professor Freedman:

Large animals enjoyed great prestige in Medieval Europe. So, lamprey and eels—some as long as 4 feet—were beloved as were sturgeon and porpoise.

Splendid birds such as peacocks were de rigueur but so were very small songbirds such as ortolans and larks. Contrary to what one might expect, beef was not highly prized, although consumed in reasonable quantity. Fresh food was more prestigious than anything smoked, salted or fermented to extend its shelf-life. At great feasts there was little in the way of preserved meat such as salt pork or cod, but in fact a lot was eaten even in noble houses on routine occasions. Mutton and sausages were associated more with moderately prosperous townspeople than with the aristocracy.

A key aspect of medieval taste was the love of piquant and varied flavors. The passion for spices, probably the best known aspect of medieval cookery, has something to do with the love of the exotic and of special effects— a taste for the exotic and for innovation which itself became enshrined as convention. The development of modern European cuisine was in reaction to medieval conventions. Modern, that is to say French, taste rejected spices as artificial, tending to cover up flavors rather than enhance them. It is a distinction of modernity that European food, until its very recent globalization and fusion, has had very little spice. Europeans have disliked aromatic tastes of the Middle East, South Asia and Africa.

Before the triumph of classic French cuisine in the 18th century, spices were dominant flavors in Europe, their aromatic appeal enhanced by the difficulty and expense of acquiring them from places so far away as to be unknown or mythologized by their European consumers. The attraction of spices is a major characteristic of medieval cuisine and conversely their ejection from European cuisine, except for desserts, by the late 18th century represents an important turning point in culinary history.

So, one can group the love of spices, color, special effects, and elaborate recipes under the heading of artifice—a theory of cuisine that emphasized sophistication over simplicity. In keeping with the love of artifice, medieval food tended to be highly processed. Raw food was seldom served in elite households until a vogue for salads started in Renaissance Italy. Even fruit was usually cooked, dried or sugared (partly for health reason—it was believed raw fruit tended to rot in the stomach and so was dangerous). There was great fondness for bright and varied colors, illusion and transformation. A common dish is described as “apples” was actually meatballs colored gold (“endorred”), or green (glazed with parsley sauce). “Eggs in Lent” were in fact eggshells drained of their contents and then stuffed with almond milk for the white, and cinnamon mixed with saffron for the yolk. Skill and somewhat vulgar effects were displayed and achieved by sculpting food to look like animals or objects, or artificially enhancing the look of animals or birds.

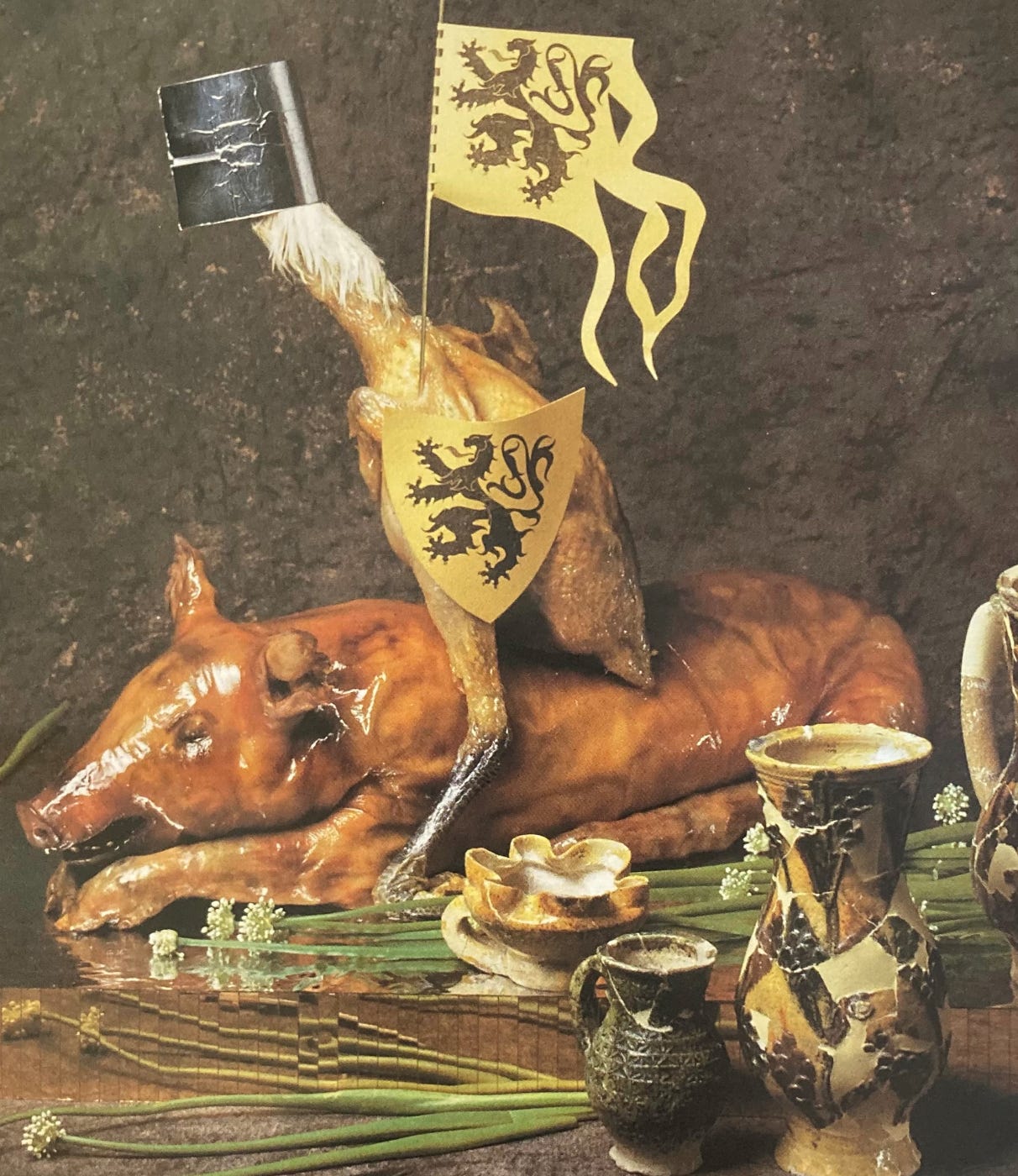

Thus, a favorite dish that appears in many cookbooks, was glazed “hedgehogs” (in England known as “urchins”), consisting of ground meat stuffed into a sheep’s stomach and then formed into a hedgehog shape with sliced almonds, often colored with different dyes, stuck along its back. Wild boar’s head was prepared with one side glazed with green sauce and the other covered with gold foil and the heraldic or mythological effect was enhanced by making it appear to be breathing fire.

A rooster was set on an orange-glazed suckling pig as if mounted on a horse, the bird being given a little metal helmet and lance. This “Armed Rooster” (coq heaumez) is found in the widely-imitated 14th-century cookbook, the Viandier attributed to the French royal cook Taillevent, nickname for the renowned Guillaume Tirel—a name later bestowed on the multi-starred restaurant in Paris, Le Taillevent.

Various soups and vegetables accompanied these dishes, but the menus fail to show much interest in dairy products, fruit, vegetables or cereals other than wheat in the form of bread. The reasons for this lacuna among the upper orders has to do with medical theories of the time and how different foods typified the hierarchical image of society.

All this changed in the course of the 15th century as cheese, formerly an emblem of rusticity, became the object of sophisticated gourmandise and we start to hear more about fruit. The first treatise on cheese as a gourmet course is Pantaleone da Confienza’s “Summa laticiniorum” dating from 1475. The fashion for salad, which began in Italy, spread to the rest of Europe by the beginning of the 16th century. Melons were all the rage during the Renaissance, though doctors warned they were dangerous even among the already perilous category of fruit. According to the usually judicious philosopher, Vatican librarian and food writer Platina, King Albert II of Bohemia and Pope Paul II died from a surfeit of melon.

It may seem as if I am describing the gastronomic lifestyles of only the stratospheric elite, but this is not really the case. Medieval cuisine was not divided simply into a gorgeous vulgarity consumed exclusively by a tiny aristocratic minority and the subsistence porridges of the peasantry. One of the largest collections of recipes from this era was assembled in the 1390s by a member of the upper bourgeoisie or petty knightly class, an elderly Parisian gentleman, author of a household and moral advice book known to posterity as the “Ménagier of Paris”. The anonymous author of the Ménagier compiled a collection of edifying stories, proverbial wisdom, household hints and some 380 recipes, all with the purpose of giving his very young wife (15 years old) instructions for how to run a household. Few men in European history ever demonstrated more knowledge about how to run a house, from keeping vermin out of bed linens to gardening to keeping fit.

Stuffed and gilded chickens he dismisses, saying “this requires too much fuss and is not the work appropriate to a chef for a bourgeois or simple knight…

The recipe collection in the Menagier is important because of the relatively modest station of the author. He was not striving for dazzling effects, nor did he expect to have a courtly public or princely cooks read his work. While many of the recipes are derived from cookbooks of great chefs such as Taillevent, the author of the Menagier rejects dishes that are too expensive or that are difficult and time-consuming—no stuffed mutton or “hedgehogs”. Stuffed and gilded chickens he dismisses, saying “this requires too much fuss and is not the work appropriate to a chef for a bourgeois or simple knight, so I am leaving it aside.” The Menagier offers recipes for precisely those items missing from the courtly world such as sausages, charcuterie, and even such humble vegetables as cabbage, turnips, and beans.

And then there's health?

A healthy dietary regime had to match the humoral qualities of particular foods with individual temperament. Beef is cold and dry, so a person with a tendency to melancholy (i.e. someone with a preponderance of black bile) ought not to eat a lot of beef. Pork and fish were conceived as cold and moist while game animals tend to be warmer and dryer than domestic animals. Young animals are moister than adults; females are moister than males. There is an almost infinite complexity to the elaboration of humoral theory.

Methods of preparation differed, so that roasting or frying made food warmer and dryer. Doctors recommended that pork be roasted because it is humorally too cold and moist, but roasting beef is less desirable since beef is already dry. Beef was preferred boiled (at least by the health-conscious) because boiling both warms and moistens. Spices were thought to be important to offset the natural qualities of basic foodstuffs. Since they tended to be hot and dry, spices were supposed to “temper” the contrary qualities found in meat, fish and game. Beef, goose, brains, tongue and other humorally cold meats required vigorously spiced sauces such as cameline (based on cinnamon).

Lamprey was the object of something approaching adoration by the aristocracy, but doctors considered it dangerously cold and moist. The fact that King Henry I of England died in 1135 a week after consuming lampreys in defiance of his doctor’s orders didn’t help the reputation of this migratory predator, but it also didn’t diminish its culinary attraction. Lampreys required a peppery sauce (pepper being hot in the fourth degree and dry in the second), and also some elaborate cooking methods. For similar humoral reasons lampreys should be immersed in wine in order to kill them, then dried and boiled in wine and water, though there are recipes for lamprey prepared in aspic or baked in pastry.

Other foods were more neutral, hence safer. Chicken, for example, required only a light sauce such as jance (wine, vinegar and burnt bread flavored with ginger and cloves). Jance is also appropriate for fried fish, but boiled fish (which retains the essentially moist and cold character attributed to fish) demands a stronger sauce such as cameline (a sharp cinnamon-flavored sauce) or an herbal green sauce.

There is something comical about medieval cuisine, but then again, the passions and fashions of gastronomy in any era can be quite amusing. The turkey-noodle casseroles and cheese fondues of the recent past are now objects of satire. Still, their desires and status symbols have historical meaning.

I have tried to give an impression of what were considered requisite attributes for cuisine in the Middle Ages. This is a sophisticated but to us rather alien sensibility. But these taste preferences lasted for centuries and were not merely, or exclusively, the product of late-medieval ostentation. Before medieval Europe, Roman cuisine had been equally enamored of the piquant, the exotic and the clever and artificial. For the period after the Middle Ages, the Italian Renaissance does not represent a radical break.

The real changes would come later and are especially clear in the case of spices. In 1648, the French princess Marie-Louis de Gonzague journeyed to Poland to meet her new husband King Casimir V. She and her entourage were dismayed at the ceremonial meals presented to them in Germany and Poland whose dishes were so strongly flavored with spices (especially saffron) as to be inedible or at least, in the words of one of these unfortunates, “no Frenchman could eat them.” In 1691, the countess of Aulnoy, a French traveler in Spain, also commented on the unpleasant reek of saffron and spices in what was being offered. Conversely the French rejection of spices was noted by a German observer in the early 18th century who remarked that his countrymen, who like well-spiced food, were going to be disappointed with the blandness of France.

Changing tastes are obvious in the cookbooks. Eighty percent of medieval recipes call for spices, usually many of them at the same time. By contrast, François Massialot’s cookbook entitled Cuisinier roial et bourgeois (1691) mentions ginger in only 1% of its recipes; cinnamon is used in just 8%.

Though his work even included diagrams on the proper placement of various courses on the dinner table ….

….such medieval prestige spices as saffron, galangal [a form of ginger] or grains of Paradise are completely absent and Massialot stated clearly that “today in France…spices, sugar and saffron etc. are proscribed” (sugar in main courses that is, as its use in desserts and hot drinks soared).

But then there is a single full meal as detailed by Massialot:

With this statement we reach the end of medieval cuisine.

To conclude, as you may have gathered, taste in food is as much a part of the life of the aristocracy as the rules of chivalry and love. I have also briefly mentioned the hierarchical social codes represented by different kinds of food such as vegetables and game. The most important historical force in all of this, however, is consumer preference. It is a cliché of world history, for example, that the desire for spices lies behind the European voyages of discovery and colonial competition, beginning with Columbus and Da Gama in the 1490s, but what created that demand, what were medieval culinary and imaginative desires, what spices and cuisine meant, are subjects that remain to be explored.

Indeed, Andelman Unleashed / Unleashed Cuisine may return to such issues in the future. Meanwhile, more recipes from our medieval kitchen!

RECIPES

Bread

Unleavened Barley Bread

8 ½ fluid ounces warm water

1 tsp salt

1 tbsp oil

2 cups barley flour

Stir salt into warm water, add oil and flour. Mix the dough evenly. Sprinkle a baking board generously with barley flour. Work the dough into a roll and cut into slices. Mold each slice into a round, flat cake about a quarter inch thick. Place the cakes onto a baking sheet lined with baking parchment and. prick with a fork. Bake for 10-12 minutes at 480 degrees. Serve hot with butter. For crisper cakes, make them thinner and bake a bit longer.

MAIN COURSES

Lasagne

dough

3 cups flour

1 cup tepid water

1 ½ tsp salt

¾ ounce fresh baker's yeast

2/3 cup freshly grated parmesan cheese

freshly ground black pepper

spice mixture

½ tsp ground cardamon

½ tsp freshly grated nutmeg

½ tsp freshly ground black pepper

1/8 tsp ground cinnamon

Dissolve yeast in a little bit of water. Proof for 10 minutes, then mix into flour. Dissolve salt in remaining water, add flour to mixture to form a dough not too stiff. Knead 10 minutes like bread or pizza dough til it's smooth and elastic, revealing tiny holes when cut with knife. Cover dough with towel and let rise for an hour in warm place. Grate cheese and prepare spice mixture. Toward the end of rising time, boil large pot of well-salted water, adding a few drops of oil to keep lasagna from sticking together. Pre-heat baking or gratin dish. Punch dough down, knead I back into a ball, roll out to an even thickness of 1/16 inch. Flour work surface liberally to prevent sticking. Divide dough two or more pieces for rolling and cutting. Cut sheets of dough into 2-in squares.

Cook the lasagne in rapidly boiling water, stirring as you add them to keep them from sticking. They're done when they rise to the surface—barely 2-3 minutes. Taste one to make sure it's done: no flour taste and elastic but not too soft. Remove lasagna with skimmer or slotted spoon. Do not drain completely dry. Place layer of lasagna on baking dish, sprinkle generously with grated parmesan, a good pinch of spices and 2-3 grounds of black pepper. Repeat until you've run out of lasagna. Top with plenty of parmesan, sprinkle with spices and pepper. Serve immediately in heated soup plates.

A staple of 14th century Italian cooking.

English Lamb Stew

1 lb 12 oz – 2 lb boneless mutton or lamb

1 ¾ cups water

1 cube chicken bouillon

2 chopped onions

1 tsp chopped fresh parsley

1 tsp chopped fresh rosemary

1 tsp chopped fresh thyme

1 tsp chopped fresh marjoram or savory

½ tsp ground ginger

½ tsp ground caraway

½ tsp ground coriander

salt to taste

1 ¼ cups white wine

2 eggs

2 tbsp lemon juice

Cut meat into ¾ inch cubes. Boil water, add chicken bouillon cube and cubed meat. Let it boil, skimming off surface foam. Add onions, herbs, spices, salt, and wine. Reduce heat and simmer for 1 ½ hours. In a bowl, mix eggs and lemon juice. Remove stew from heat and carefully add egg mixture.

Recipe originates in the Forme of Cury, among the oldest works of English cookery, dating to the "chief Master Cooks" of King Richard II (1377 til he was deposed in 1399).

Sauce

Good All-round Sauce

¾ - 1 pint chicken stock

5 fl oz beef stock

6 tbsp croutons (plus or minus)

½ tsp ground pepper

½ tsp ground caraway

pinch ground saffron

salt

Combine chicken and beef stock, bring to boil, add croutons and spices, again bring to boil. Lower heat to simmer briefly. Remove from the burner, strain. Use immediately or refrigerate for future.

Origin: 15th century England in the Noble Boke off Cookryn.

Dessert

Almond Cream

4 ½ ground almonds

½ cup water

½ cup sweet white wine

1 ½ cups cream

3 tbsp sugar

1/3 tsp salt

Boil ground almonds in water for a moment, stirring. Add wine, salt, sugar, cream. Cook over moderate heat, stirring til thickens and becomes creamy. Sieve mixture, add more sugar if needed. Serve chilled. In refrigerator it will thicken further. May be served with pies or fresh fruits, berries.

Often offered at the start of the third course, followed by fritters, at the wedding banquet of Henry IV of England and Joan of Navarre in 1403, served at the end of the meal were almond cream, pears in sugar syrup, cream puddings and pastries.

These and other recipes may be found in Hannele Klementtilä, The Medieval Kitchen: A Social History with Recipes (Reaktion Books: 2012)….and Odile Redon, Françoise Sabban & Silvano Serventi, The Medieval Kitchen: Recipes from France and England (University of Chicago Press: 1998)

This brings us to an end of our exploration of Medieval Cuisine. For Part I, if you've missed it, click here. Be sure not to miss our next culinary adventure on Andelman Unleashed….and of course our regular weekly exploration of the world around us—how others view America and themselves.

Finally, we've just arrived in Paris for the debut of the Games of the XXXIII Olympiad. Stay tuned!

Love the recipes. Brilliant.

Trying to imagine the Lasagna that contains only parmesan and am wondering if the texture and dryness was similar to the parmesan we have today. Did they sort and store by age? Seems like the lasagna back then was on the dry side. These days in Italy, it's common to use ricotta and parmesan. Did ricotta exist in the Middle Ages? Personally, I love going into a country story in the Siena area and asking for a 'taste' of the various cheeses. Those small stores tend to be generous in many ways that supermarkets are absolutely not!